Hidden thoughts of a visual nature

Art at the origin of psychoanalysis

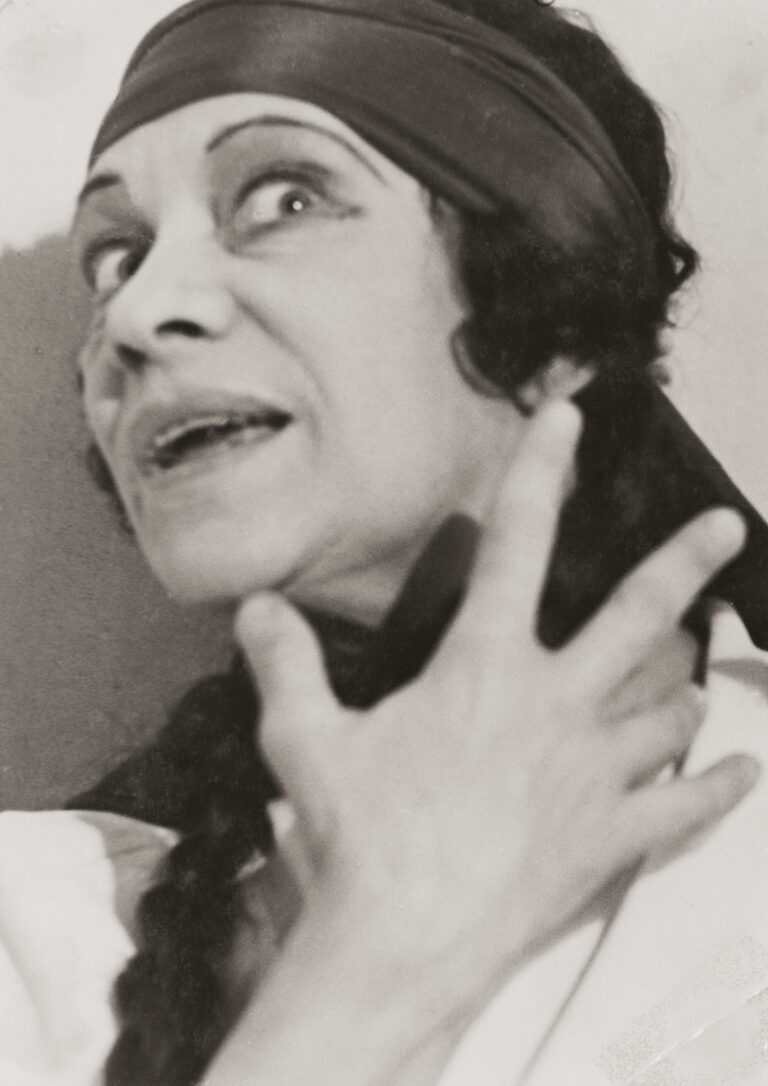

Monika Pessler is the director of the Sigmund Freud Museum, which will reopen in September 2020 after extensive renovation and expansion measures. For the first time, all of the family’s private rooms will be accessible, and a collection of conceptual art will be on display in the former ordination rooms.

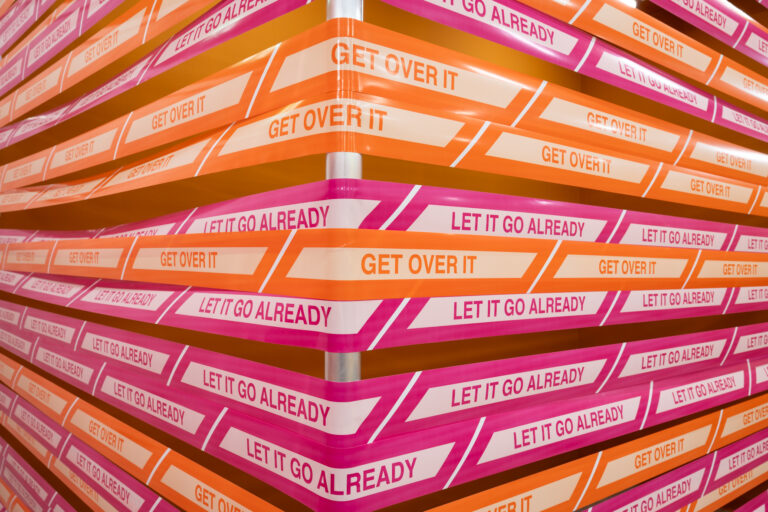

Ausstellungsansicht: Verborgene Gedanken visueller Natur © Oliver-Ottenschlaeger, Sigmund Freud Privatstiftung

Sigmund Freud lived and worked in the house at Berggasse 19 from 1891 until his escape from the National Socialists in 1938. Today the former living and practice rooms house the Sigmund Freud Museum, which includes original Freud furnishings, a library and an extensive archive. After one and a half years of renovation work, the Sigmund Freud Museum has been shining in new splendor since August 29, 2020.

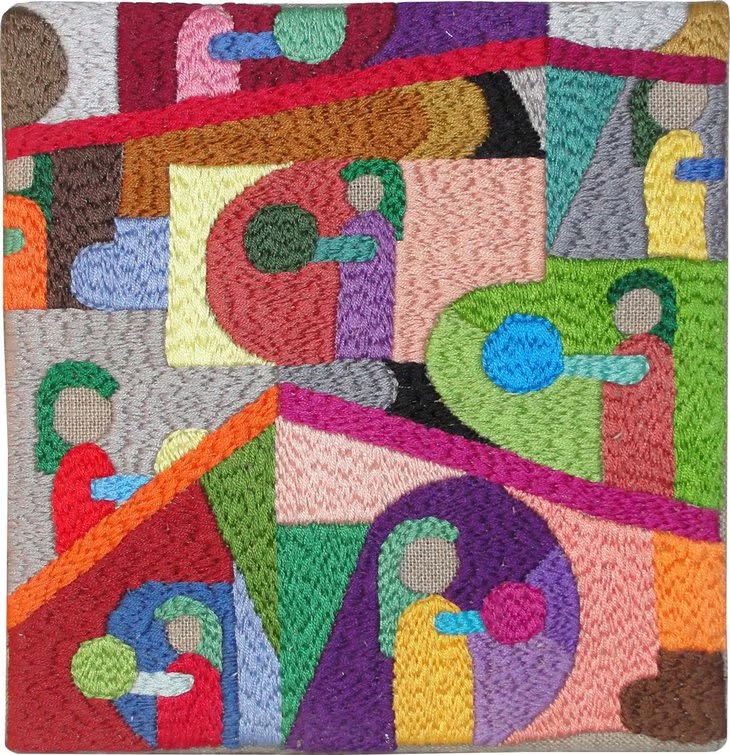

The former ordinations still breathe the aura of the early developmental history of psychoanalysis, and the rooms on the mezzanine floor, where Freud ordained from 1896 to 1908, now house a small but fine collection of conceptual art. Monika Pessler, director of the Sigmund Freud Museum, talks about what awaits visitors to the exhibition of conceptual art.

Director Pessler, the Sigmund Freud Museum’s collection goes back to the room installation “Zero & Not”, which Joseph Kosuth realized in 1989 to mark the 50th anniversary of Sigmund Freud’s death. Can you tell us more about this work? What role does Kosuth play in the creation of the collection?

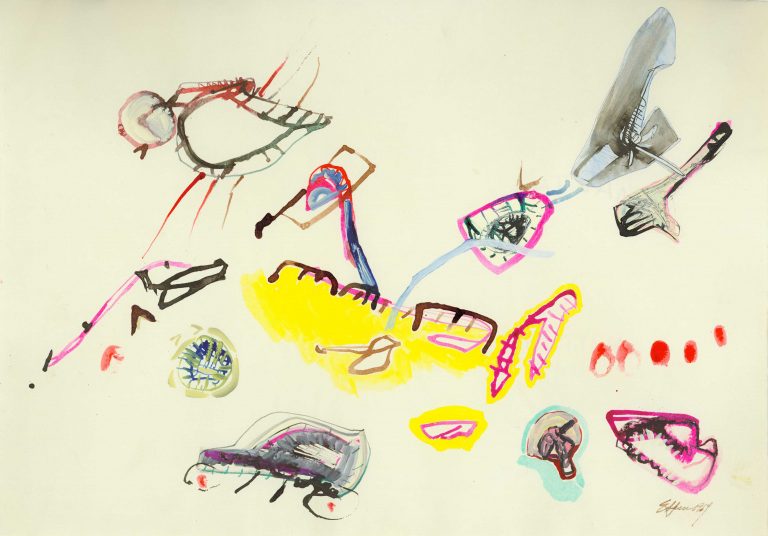

Monika Pessler: When Joseph Kosuth realized the installation “Zero & Not” at Berggasse 19 in 1989, he invited international artist colleagues to participate: In front of text passages from Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams on the walls – some of them crossed out beyond recognition – works by Ilya Kabakov, John Baldessari, and Pier Paolo Calzolari, among others, were on view. These works were subsequently donated to the museum by the artists. On the occasion of a further presentation in 1997 and an exhibition in the 21st House of Belvedere in 2014, the art collection was expanded by further donations – including works by Sherrie Levine, Haim Steinbach, Heimo Zobernig, Wolfgang Berkowski and Susan Hiller, to name but a few. Joseph Kosuth was the founder of this art collection and initiated a “living monument”, as he put it, to represent the influence of psychoanalytic ways of thinking “on the cultural horizon that forms our consciousness”.

Monika Pessler, Photo: Stephanie Letofsky © Sigmund Freud Privatstiftung

What do psychoanalysis and art have in common?

Monika Pessler: In their methods and approaches, numerous parallels open up for us between the arts and psychoanalysis. Freud himself describes these – especially with regard to the fact that psychoanalysis, like art, often pays attention to details that are not given much attention – suppressed and hidden mental states, for example. In Freud’s description of “dream work” in particular, the proximity between psychoanalytic views and artistic approaches becomes evident, since the visualization of “hidden thoughts” in dreams, the creation of “dream images”, is not dissimilar to the pictorial manifestations of Conceptual Art.

The exhibition entitled “Hidden Thoughts of a Visual Nature” uses the spatial structure of Freud’s “first” ordination, which has been preserved in its original form. What awaits us in the individual rooms?

Monika Pessler: With the original preserved architectural structure of Freud’s former place of work, not only is the “place of origin of psychoanalysis” clearly defined. In addition, the contents that once occupied Freud here correspond to those of the exhibited works of art:

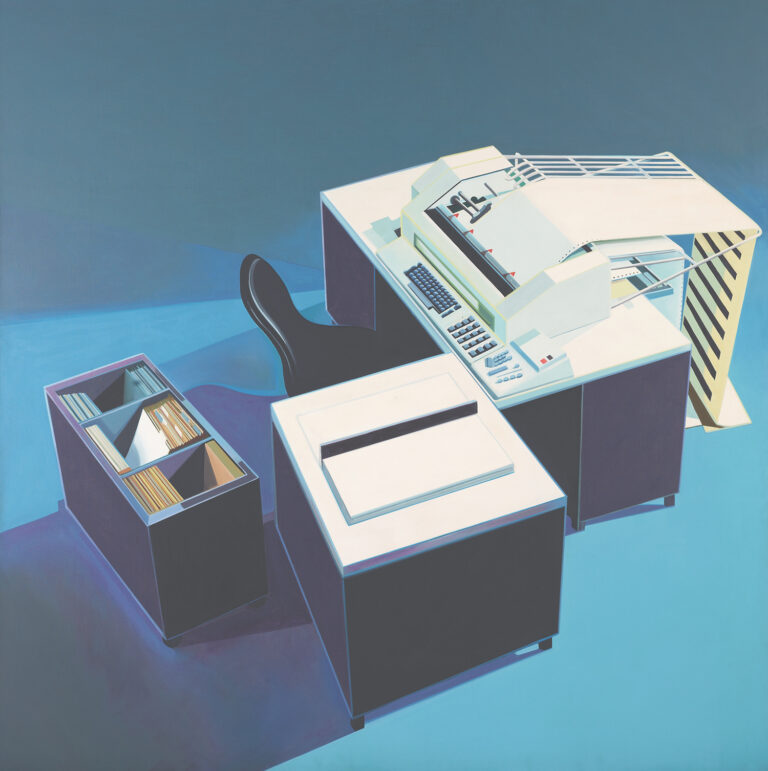

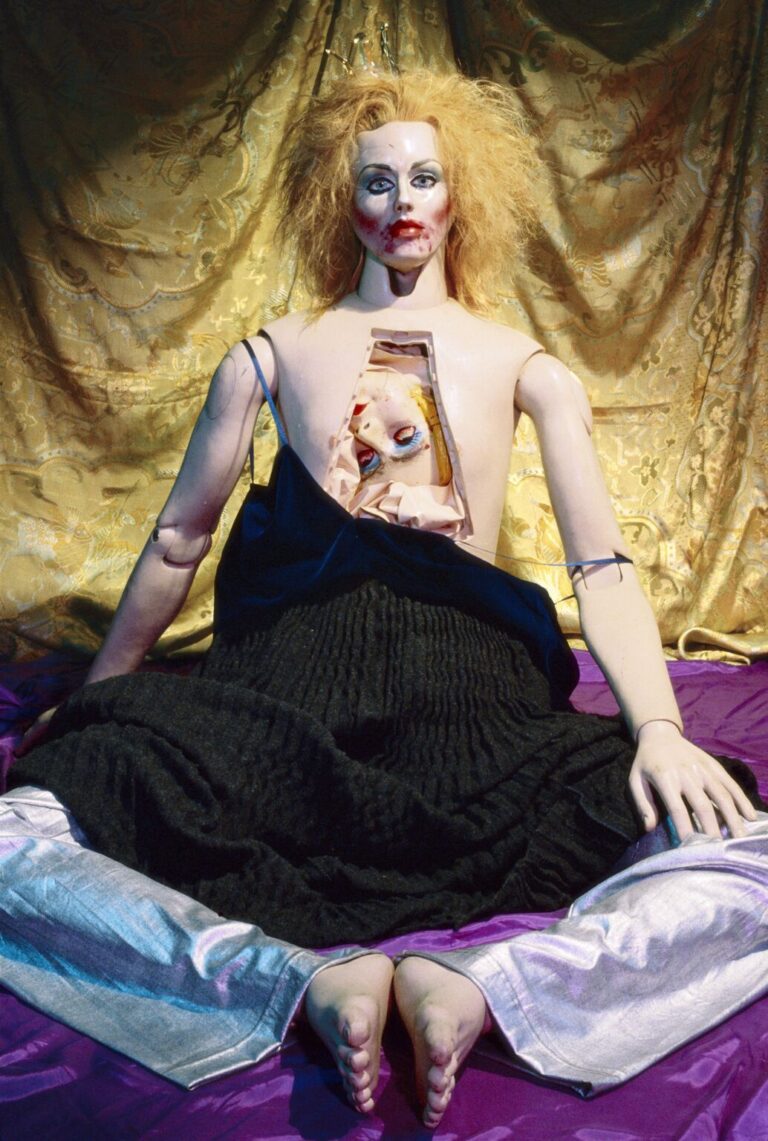

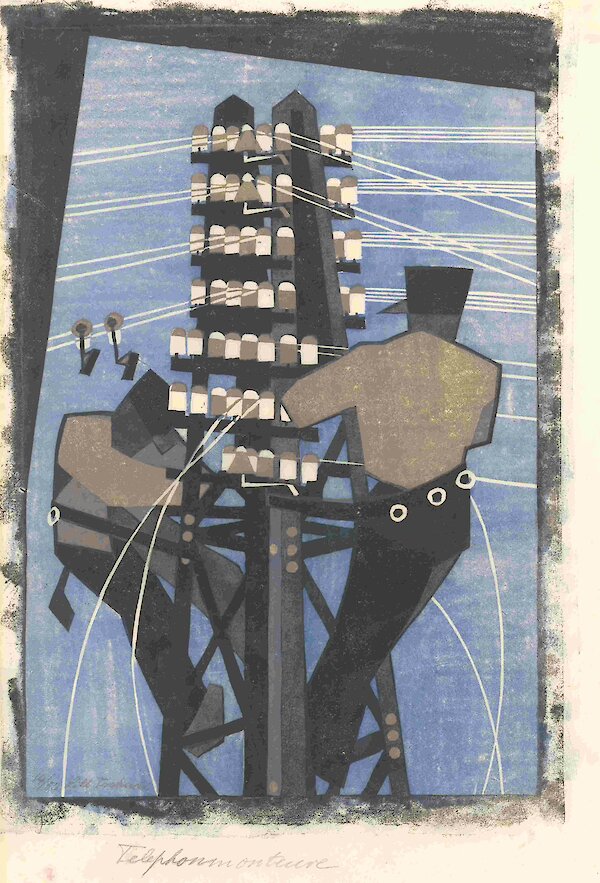

In the waiting room, Kosuth’s work O. & A./F!D! (TO I.K. AND G.F.), which refers to Freud’s text Der Witz und seine Beziehung zum Unbewussten, is juxtaposed with Heimo Zobernig’s work, which, based on a quotation from Freud’s letter, ironically addresses the representational power of monuments. In the adjoining treatment room, works by Franz West and Haim Steinbach comment on the phenomenon of psychoanalytic settings – the icon of the couch and the so-called “Talking Cure”. Georg Herold devotes himself to the art-historical subject of “Amor and Psyche”, while John Baldessari contributes to the chapter on the “uncanny”, which Freud dealt with intensively. As an artist and researcher, Susan Hiller documents her work on the Freud Archive at the Freud Museum in London. On the veranda, Wolfgang Berkowski and Sherrie Levine comment on the theme of memory and mourning work. In Freud’s former study, where he wrote the Interpretation of Dreams, there are two works which, like the founding document of psychoanalysis, are strongly autobiographical in character.

Gender difference and desire are the focus of Pier Paolo Calzolari’s wall installation “AVIDO” in the kitchen of Freud’s practice.

In this way, the presentation spaces of art represent a correlate of its concepts and vice versa. This mutually corresponding relationship between the exhibits and their surroundings is revealed in the course of the visit to the “physician’s apartment”, which with all its attributions of meaning becomes an exhibition display.

Is the show in the consulting rooms designed as a permanent exhibition? What are further plans for the collection and the exhibition rooms?

Monika Pessler: For the time being, the works of the Conceptual Art Collection will be on permanent display here, until perhaps one day a further reconstruction of the building will make it possible to expand the exhibition space further, so that the mezzanine floor alone can be used for the historical narrative of the early developmental history of psychoanalysis and the art can be exhibited in its own rooms according to the principles of the “white cube” – whether this would actually bring about an improvement or progress, however, I dare to doubt at this point in time. We still have to think about that.

Art often touches us in a very personal way. Which of the works is particularly close to your heart?

Monika Pessler: “AVIDO” by Pier Paolo Calzolari in Freud’s former kitchen – and, of course, the current installation by the American artist Robert Longo in the “Schauraum Berggasse 19” from his 2011 series “Monsters”. Since the late 1990s, Longo has preferred to work with coal. The exhibited print of his charcoal drawing “Untitled (Hellion)” was created at the same time as the “Freud Cycle”, in which Longo intensively studied historical photographs of Freud’s place of work. In the high-contrast black-and-white drawing of a breaking wave, threat and danger openly emerge. According to Longo, the image of the “indomitability of the oceans” in comparison to the “Freud Circle” represents a counterweight to “human reason” as reflected in the images of Freud’s surroundings. The title “Hellion” (“Devil’s Roast”) in brackets also underscores the possibility of the unpredictable unleashing of inner forces: the large, eerie, beautiful water formation becomes the epitome of violence and destruction that breaks free of meaning. Robert Longo’s metaphorical approach not only testifies to his artistic interest in the psychic dimensions of human consciousness and therefore seems to fit in well with “Schauraum Berggasse 19”. The image of a wave, which – although captured behind glass – threateningly exceeds the horizon of the viewer, provides an expressive visual counterpart to our current individual and collective fears in times of the Corona crisis.

Finally, two questions about the Sigmund Freud Museum in general. What was the greatest challenge during the reconstruction?

Monika Pessler: It’s difficult to answer and to judge, but the distance to this project, which has been intensive over several years and on so many different levels, still seems too small to me. I think the step from conception to realization was the most exciting, but what does that mean?

What are you particularly looking forward to after the reopening?

Monika Pessler: To further projects at and in this Haus-Museum, which as the “place of origin of psychoanalysis” can make a meaningful contribution to our current and socio-political questions.

(Interview: Barbara Libert)