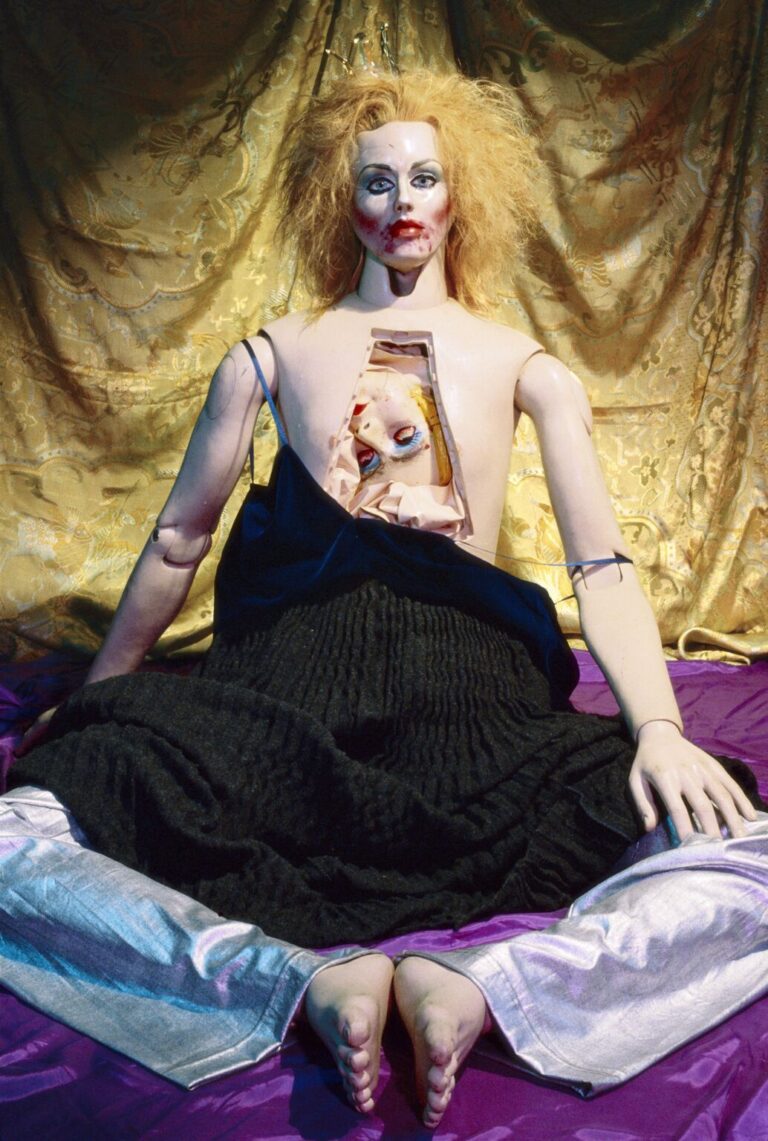

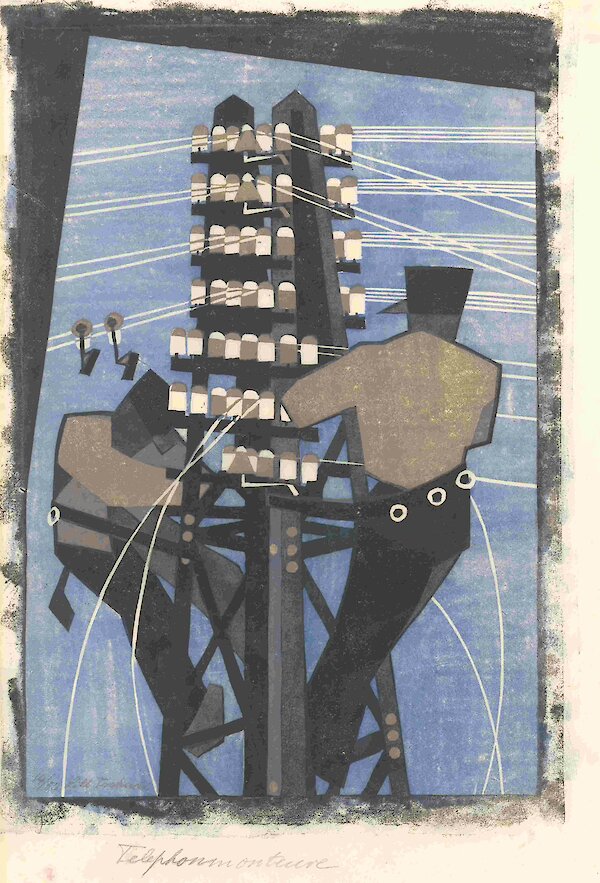

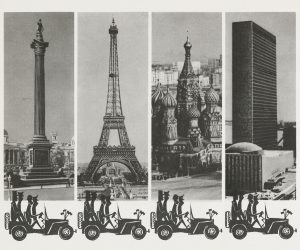

Die Vier im Jeep © llustration Epi Schlüsselberger, Georg Schmid, in: Ernst Marboe: Yes. Oui. O.k. Njet, Wien, 1954[/caption]

[caption id="attachment_3364" align="aligncenter" width="728"]

Die Vier im Jeep © llustration Epi Schlüsselberger, Georg Schmid, in: Ernst Marboe: Yes. Oui. O.k. Njet, Wien, 1954[/caption]

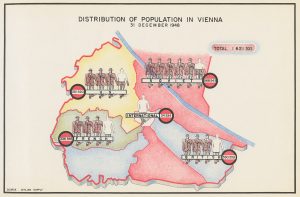

[caption id="attachment_3364" align="aligncenter" width="728"] Verteilung der EinwohnerInnen in den Besatzungszonen Wiens © in: United States Forces in Austria, Austria. A Graphic Survey, 1949[/caption]

Verteilung der EinwohnerInnen in den Besatzungszonen Wiens © in: United States Forces in Austria, Austria. A Graphic Survey, 1949[/caption]