Watching the film—composed of four lengthy shots of people reading, interspersed with short excerpts from their chosen books—you occasionally get the feeling of staring into a mirror, with the subjects’ rhythm of perusal, reexamination, and contemplation bearing a close and slightly uncomfortable resemblance to your own.

The first reader, Clara McHale-Ribot, is making her way through D. H. Lawrence’s Women in Love, but this doesn’t become apparent until at least the ten-minute mark, when she shifts her position and exposes the book’s jacket to the camera for a short while. And so on for each of the four shots, featuring, in order, the author Rachel Kushner, the sociologist Richard Hedbige, and the performance artist Simone Forti.

It’s tempting, when writing about READERS, to stop at recreating the hypnotic feeling of watching the film. But this can give the false impression that Benning’s direction is nonexistent instead of just skillfully restrained; that his craft consists of turning on the camera and waiting for his viewers to do the hard work. A more accurate statement would be that Benning, aims to foster and celebrate the artistry of other people without compromising his own—a goal hinted at in READER’s cast of world-class thinkers and creators. This desire to connect with the ordinary, adventurous viewer also seems to have played a part in the director’s switch from 16mm to digital a decade ago.

Benning’s artistry is most visible in READERS at those moments when the film jumps between ways of seeing. In each short period following a shot of a reader, after we’ve spent oh-so much time scanning the frame at our own pace, we’re suddenly forced to read for ourselves, right to left and top to bottom. The effect is jarring but invigorating and even a little funny, lying somewhere between a non sequitur, a big reveal, and a punch line.

Benning’s four readers engage in a practice that’s becoming rarer with each passing day: spending time by themselves, sans electronic distractions of any kind, and pondering. By celebrating this, Benning’s output offers the ultimate rebuttal to slow cinema’s detractors. How can patient contemplation be trivial when it’s going extinct?

(quot. Jackson Arn, Long, Hard Looks, 2018)

Please feel free to contact the gallery for further information!

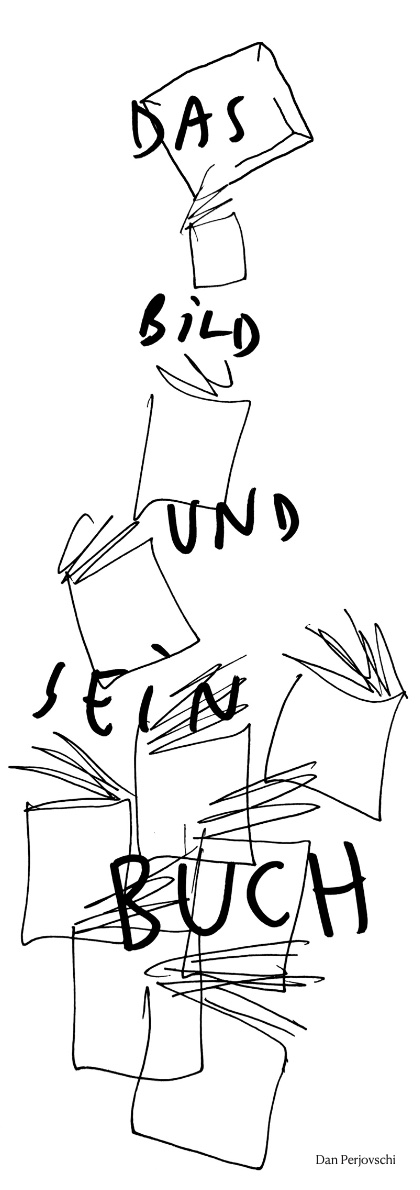

Christine KÖNIG | CHAPTER III: DAS BILD UND SEIN BUCH

THE PICTURE AND ITS BOOK: Two forms of narration, two forms of perceiving the world. While the viewer of an artwork is mostly overwhelmed with an abundance of information, the book invites contemplation. The interplay of these two aesthetic dispositives enables the connection between time and space. In this way, the traditional format of “exhibition” is raised above itself. But it is not only about books that influence artists and their works, it also may refer to single words that literally wander into the picture. Joseph Kosuth for example, took over individual terms from Thomas Bernhard’s novel “Correction” and transformed them into a light installation corresponding to the area of the printed page.

THE PICTURE AND ITS BOOK thereby unfolds a “Glasperlenspiel” that manifests itself on a variety of levels. “Reading means dreaming through hands of a stranger”, Fernando Pessoa once wrote. One could also reverse the formulation: “dreaming while observing art, means reading through hands of a stranger”. (Thomas Miessgang, 2024)

CHAPTER III: James BENNING | READERS

24 Oct 2024 - 30 Nov 2024

Christine KÖNIG | CHAPTER III: DAS BILD UND SEIN BUCH

Schleifmühlgasse 1, 1040 Wien, Österreich