Nicoleta Auersperg

In cooperation with studio das weisse haus.

Nicoleta Auersperg,

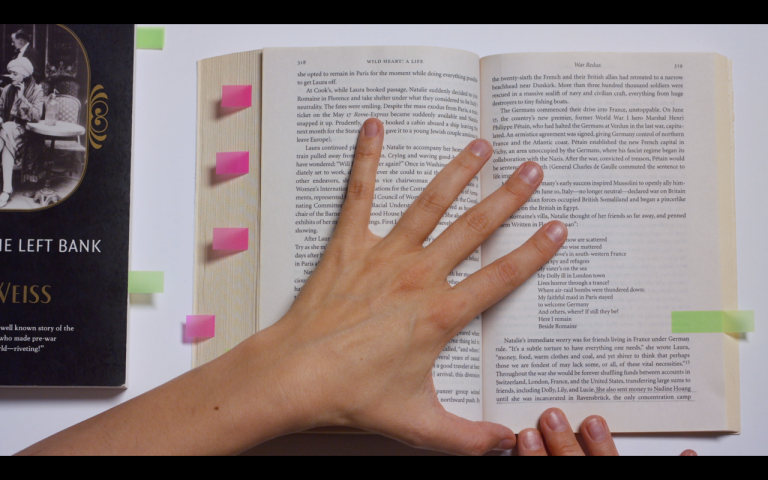

Nicoleta Auersperg and I met in her studio, adjacent to the artist-run space GOMO. With a hearth-like heater set up in the corner, we sat down for some tea and to talk about her current work, key themes in her practice, and upcoming projects.

Drinking tea, Auersperg explains, is her daily studio ritual – sitting down for a few minutes, having tea, and making a brief plan for the day. It allows her a moment to switch gears from everyday life – characterized by administrative and organizational tasks – to studio life.

As we sipped our tea and also began to settle into studio life, we first took a look at the work that Auersperg created while in Berlin during the first lockdown earlier this year. Titled “Leave to Rise”, the work was discussed by Auersperg during her digital open studio, within the frame of Vienna Art Week’s theme of “Living Rituals”. It is based on a social phenomenon Auersperg began to observe during the lockdown: baking bread. While in lockdown, the people around her, on social media, and even Auersperg herself, it seemed, started to bake bread – even if they had never done so before.

Thinking through this sudden shift in everyday routines, Auersperg puts forth: “When your job is taken away, it is something that gives you a feeling of productivity – and it is also something you can share: with others to eat, as well as on Instagram. It has something to do with social fulfilment.”

Nicoleta Auerperg, Leave to Rise, 2020

A translation of material and process occurs in “Leave to Rise” via the interaction between plaster and wicker. Auersperg used plaster to create the base of the sculptures – rounded forms in different shapes and sizes intended to evoke dough leavening baskets used for different types of bread. The ringed texture that is characteristic of the baskets is reproduced in plaster, around its sides; though, on top, it takes on a more dough-like quality – smooth and imperfect like unbaked bread. Rising up from this doughy surface are single strands of wicker, the tips of which match the color of the plaster base from which they rise. The work was featured in a public sculpture route, exhibited on the ground outside of the Columbia theater in Berlin – the building’s form amplifying that of the baskets. Placed in this way, around the entrance of the building, the objects evoked potted plants. It’s an association that resonates as we sit in the studio, with one of the pieces from “Leave to Rise” resting next to our tea cups and a bowl of fruit. And, as Auersperg points out, it’s another reference to processes of rising, of growth.

There are a few things occurring in this work that can be seen as emblematic of Auersperg’s practice more broadly. Namely, a focus on material processes, translations of form, and architectural correspondences. In a number of her works, processes manifest as potential –as in, the possible interactions, reactions and transformations that materials could perform. This is visualized, for instance, by the side by-side placement of plaster and water contained in plastic bags, unable to touch. The artist elaborates: “In general, my work is process-focused – it’s about the process within materials. I sometimes call it potentials, or what they are able to do or perform. In a lot of works, I try to freeze this process into static objects.”

Nicoleta Auersperg, Einbein

As with “Leave to Rise”, at times these processes are not only catalyzed by physical reactions, but social, as well. In another public installation, “Einbein” (2019), as part of Berlin Project Space Festival, Auersperg’s steel sculptures were placed outside for viewers to sit on during a reading performance. The welded steel objects were rested on their circular bases with rods pointing upwards, prompting audience members to flip them over in order to take a seat – thereby transforming them into one-legged stools. The steel discs bear heat marks, revealing welding process, while their structure alludes to the functionality of milking stools, which facilitate balance in a squatted position. Balance, Auersperg explains, also plays a significant role in her practice.

In the context of these interactive sculptures, balance – embodying a sense of fragility – is a response to a particular precariousness in public space. The spikes that point upward when the objects are in their resting state are reminiscent of defensive architecture in urban spaces. A pervasive phenomenon, the use of such harsh structures hinders people from finding refuge or rest in public space, engendering a hostile environment. It’s a rejection of bodies, of softness, that inevitably molds us. For Auersperg it is a question of how we might be able to deal with this: “Somehow we are shaped by public space. What’s our potential to be subversive?”

In “Einbein”, this notion of social molding is further linked to another molding process. In the relationship between the rounded shape and the long rod, the objects’ form materializes an association with glassblowing – another mode of making that is prominent in Auersperg’s practice. As Auersperg points out, with glass, as an applied art, there is always a functional aspect. And for her, the question of functionality also plays a central role. We might, in fact, consider this another moment of subversion that emerges in her work – as with the steel objects, which in one position offer a place to sit and in another act as a deterrent against it.

Nicoleta Auerperg, Hot to the Touch Photo: Peter Mochi

In a similar way, Auersperg’s “Squatters” – bulbous objects made of mouth-blown glass attached to multi-colored steel platforms that protrude from the wall – similarly evoke an unmet functional potential. Taking on a playful dimension, the glass objects are vessel-like,suggestive of glasses, vases, or lamps; but they are destabilized, irregular in shape, appearing to droop or slip down off of their perches. Their edges are also left rough, as Auersperg forgoes a smooth finish in order to further distance the objects from their functional possibilities.

On a thematic level, questions of work, labor, production and productivity – what type of work is acknowledged and how – also come into play in Auersperg’s practice. It’s a topic that has, of course, become increasingly relevant, not only as a result of the pandemic, but also due to the changing nature of work in the digital age.

When asked what she is currently working on, Auersperg gestures towards a wooden chair near the corner of the room. This particular chair is not necessarily her focus, however its form is similar to the bentwood chairs with hand-woven wicker seats produced on a large scale by the company Thonet from the late 19th century. Drawn to the material processes behind their creation – which involve steaming and bending beech wood – Auersperg observed that such chairs are now being thrown away. As Auersperg explains, the cost of repairing the wicker structure is considered, by many, to be too high – especially given that other options exist. For Auersperg, the current disposability of these chairs highlights the effects of globalization, as well as digitization, and the role they play in the transformation of work life and the sectors that are considered important – and therefore receive acknowledgement, i.e., via compensation for their labor. In this way, in her latest project, she will be continuing her work with wicker and its material processes, while considering shifting notions of labor and the way it is valued.

Meanwhile, in addition to her studio practice, Auersperg also collectively organizes GOMO – along with Mara Novak, Dorothea Trappel and Marit Wolters – through which a group exhibition is set to open in Düsseldorf in February. The two forms of work, carried out in the studio and the space, require their own balance, of course – parallel processes of liquidity, molding and finding form, of slipping fluidly between functions, perhaps facilitated by a cup of tea.