Not just a piece of the coat

Limo Bob in his office, Chicago, 2008. Bob owns a 100-foot limo that made the Guinness Book of World Records for being the world’s longest limousine.

We remember: In the spring of 2020, at the beginning of Corona, there was still little talk of social inequality in the media crisis discourse. Before the virus, the tenor was, everyone was equal, regardless of bank balance, profession and social status. Poverty and precarity remained what they had been before the pandemic: media black boxes. One year – and several lockdowns – later, things looked somewhat different. Corona, they read, had shed light on the ever-growing gap between rich and poor. For the first time since the financial and euro crises, the question of who has what and how much (and what privileges and opportunities for influence go with it) was once again increasingly in the focus of public debate. Calls for redistribution and even expropriation were heard (“Let the rich pay for the crisis!”). Whether these are the beginnings of a progressive turn in the current crisis or just discursive flashes in the pan that will quickly fizzle out is still open. The only thing that is certain is that things cannot go on as they are.

The Dom Museum Wien has also recognised that the topic of inequality has gained urgency and deserves increased attention. “Poor & Rich” is the – simple but sympathetically direct – title of the current annual exhibition curated by museum director Johanna Schwanberg. The exhibition’s claim is to “put its finger on the wounds”, namely, on the problem of the ever-widening gap between rich and poor worldwide. The decision for the theme was made in mid-2020. “In view of the increasing social aggravation in the wake of the pandemic”, says Schwanberg, it would have been obvious for the Dom Museum to make an exhibition about “socio-economic inequality” – taking into account both moments, poverty and wealth, and with the aim of interweaving different artistic perspectives on the theme, “juxtaposing old and new, profane and sacred”, as Schwanberg emphasises.

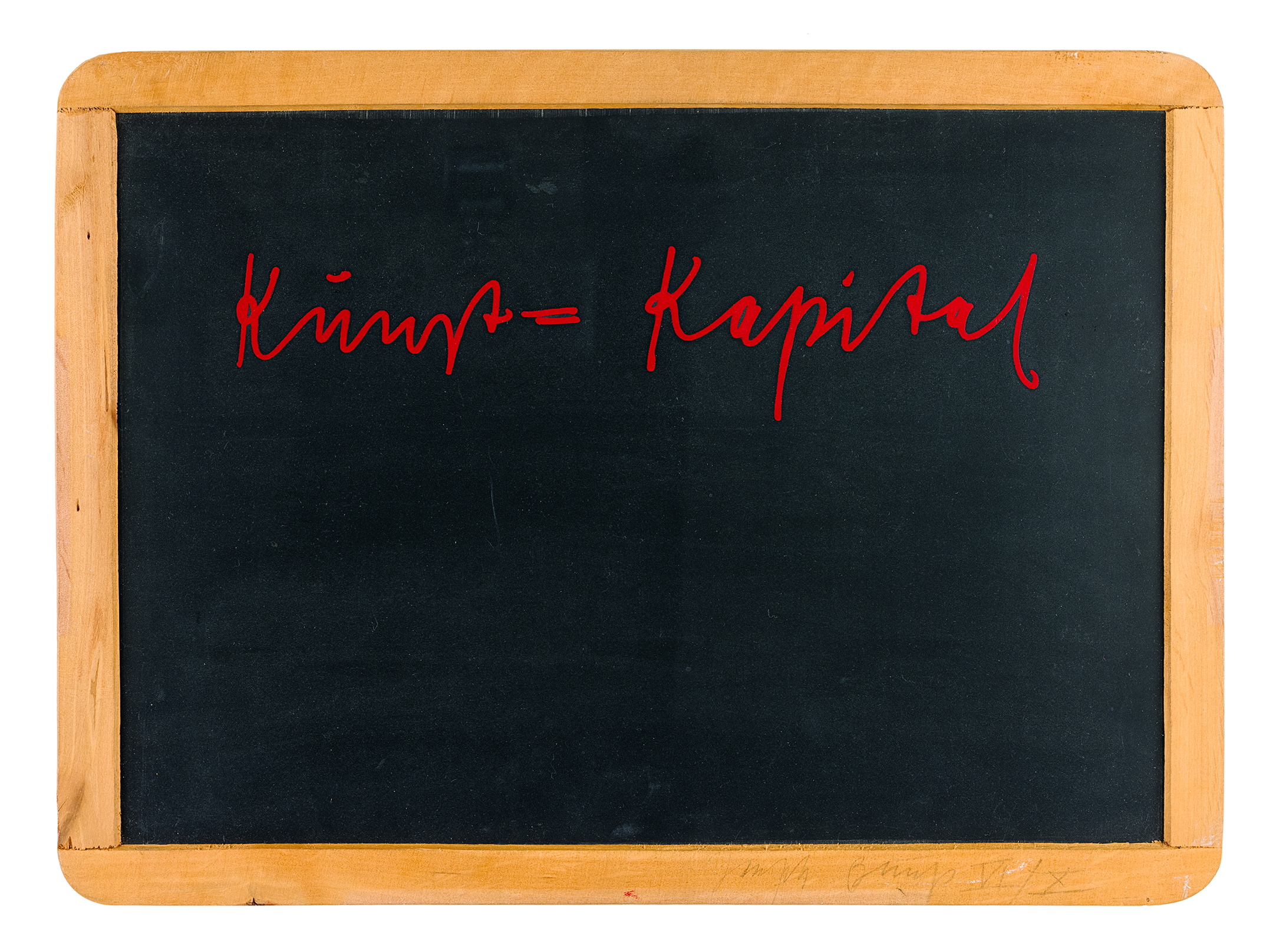

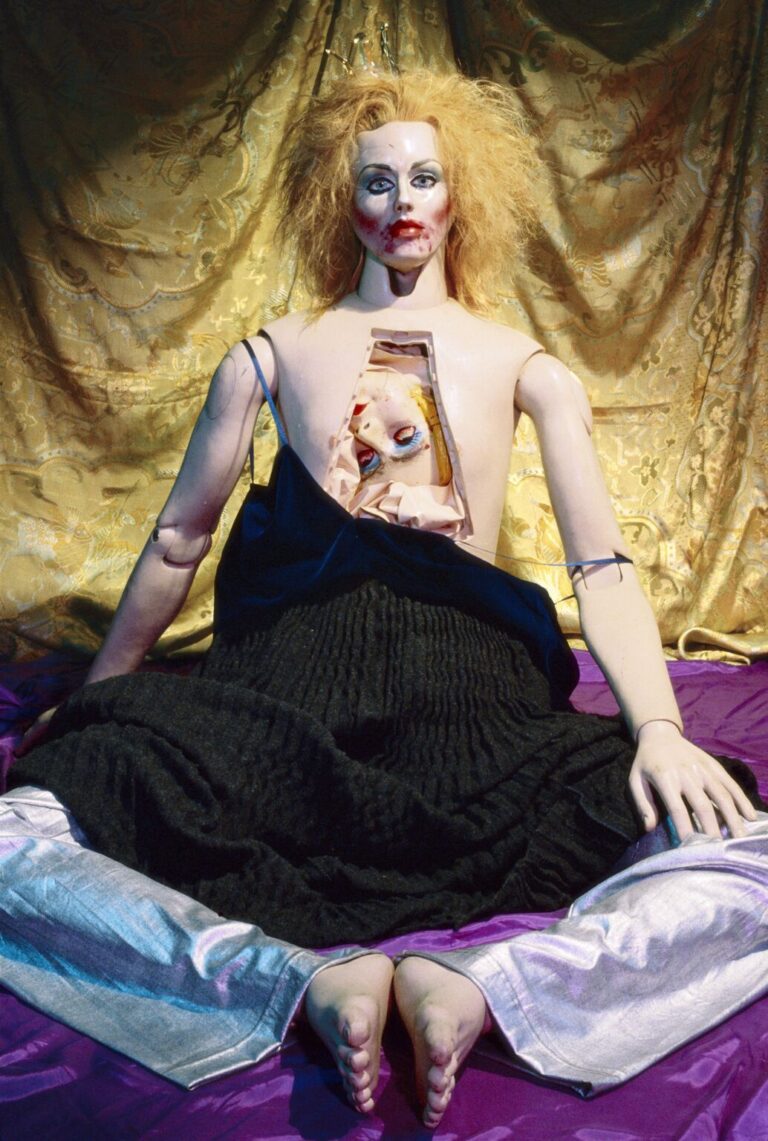

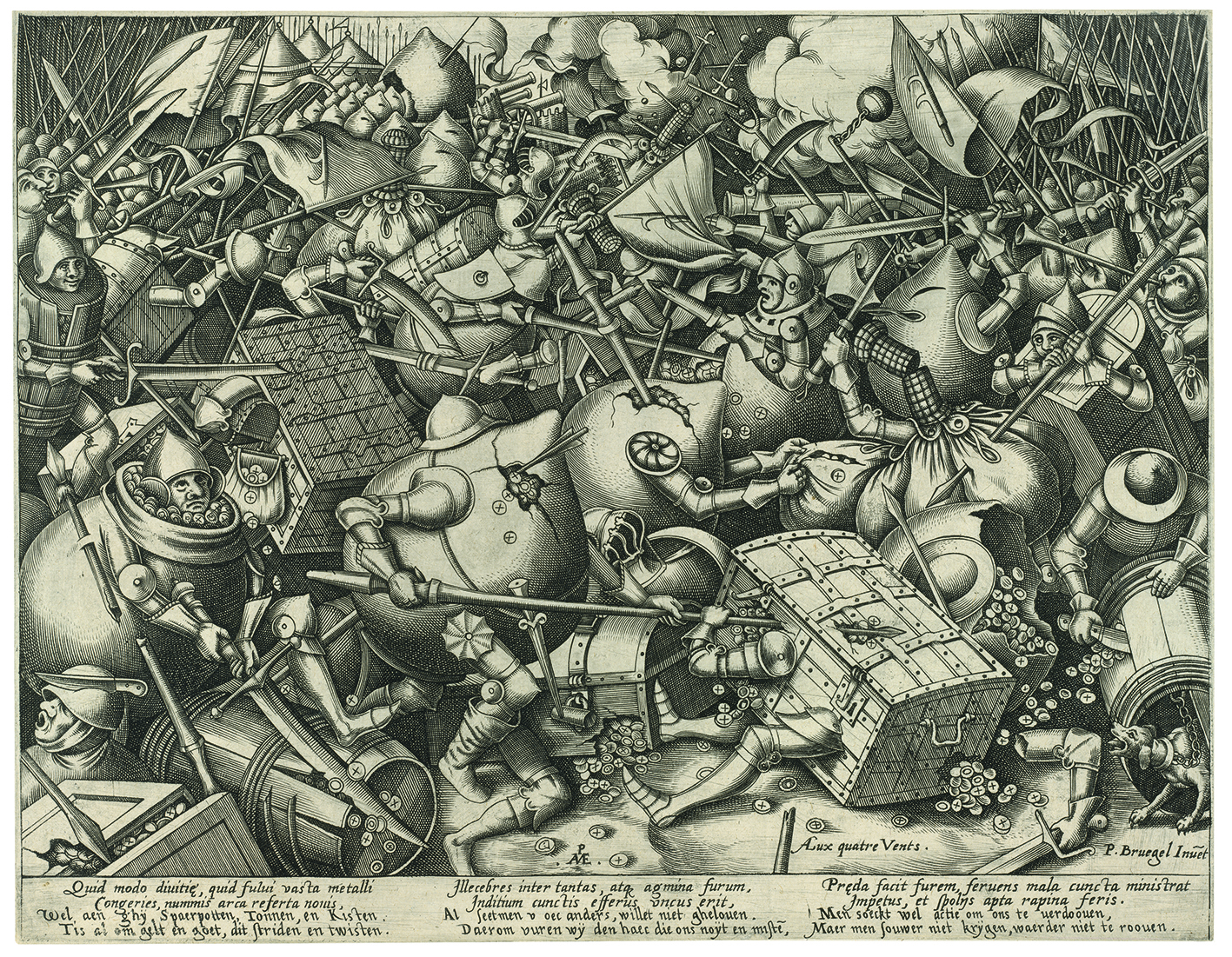

A glance at the list of works shows: The exhibition is indeed not lacking in encounters between old and new. In addition to numerous major and minor big names from modern and contemporary art (Joseph Beuys, Nan Goldin, Rosemarie Trockel, etc.), the names of artists from the Middle Ages, Renaissance and Baroque (Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Albrecht Dürer, Rembrandt van Rijn, etc.) are also to be found in “Poor & Rich” – as a matter of course. A constellation that makes one curious, but also sceptical: what can be expected from such an eclectic selection?

Pieter Bruegel d. ƒ., Kampf der Geldkisten und Sparbüchsen, nach 1570. Albertina, Wien. Foto: Albertina, Wien

Thematic art exhibitions – with a socially critical slant – are always tightrope walks. On the one hand, it is important to do justice to the complexity of the theme, and on the other hand, to the peculiarities of the selected works. Often, the explosive nature of the theme threatens to steal the show. In “Poor & Rich”, the Dom Museum counters this danger with an idiosyncratic, but in view of the exhibition theme (“Wealth”) quite sensible counter-strategy: a lot of art. Photographs, graphics and paintings hang closely together in the four exhibition rooms. In addition, there is a selection of sculptural, installation and film works. This has the double-edged effect that, on the one hand, there is indeed a lot to see and discover in “Poor & Rich” – including a lot of good stuff – but, on the other hand, one quickly loses the overview.

For better orientation, the exhibition is divided into six thematic areas: “The Big Gap”, “Faces and Stories”, “Criticism, Resistance and Protest”, “Places of Inequality”, “Symbols, Materials and Values”, “Sharing and Participation”. The (ambivalent) status of poverty in the Christian tradition is also a recurring theme. Already in the first room (“The Big Scissors”) we encounter a key motif of Christian charity: a depiction of Saint Martin sharing his coat, dated 1502. Unusual for the motif, the saint is depicted together with two beggars (one “worthy” and one “unworthy”), whereby he naturally shares his coat with only one of them. The other goes empty-handed.

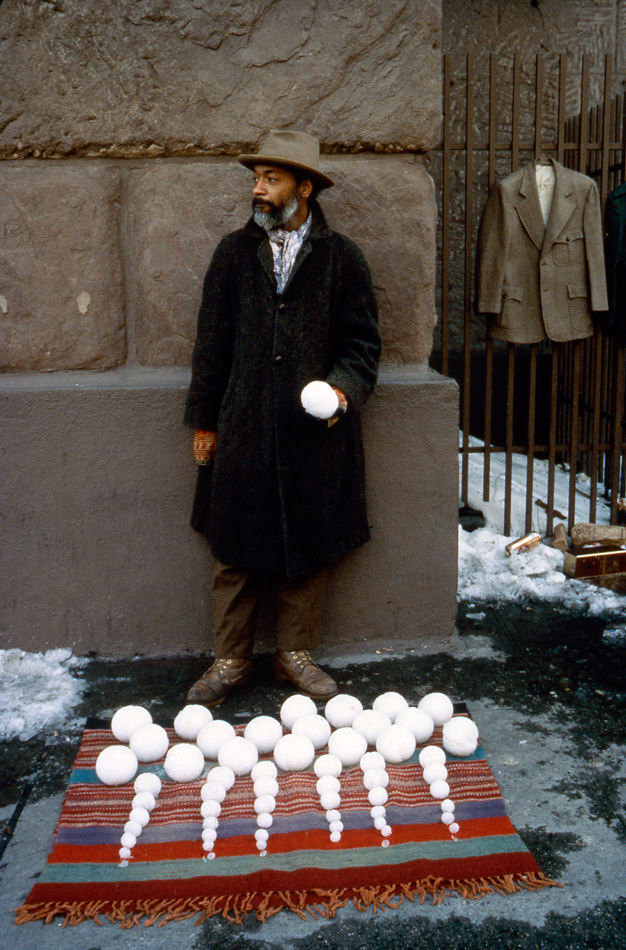

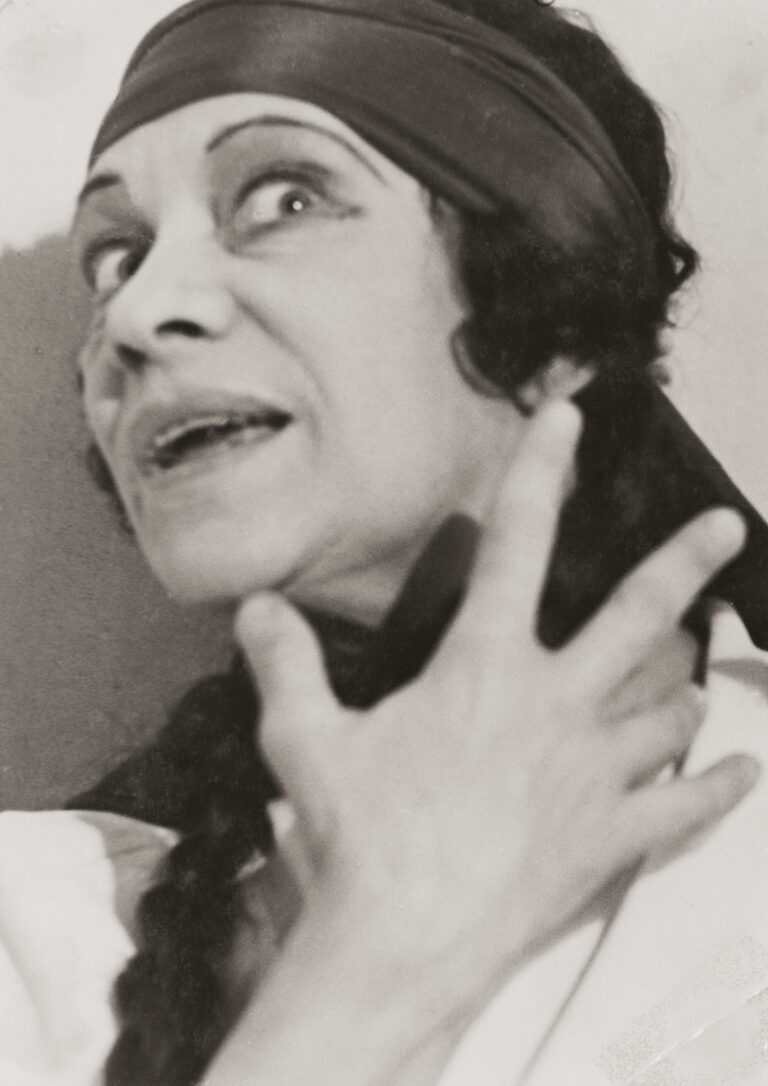

The set-up in the next room (“Faces and Stories”) seems a bit schematic. On one side we see portraits of social elites (or people who are considered to be such), for example a portrait of Napoleon Bonaparte by Andrea Appiani, together with a photo series by Lauren Greenfield “Generation Wealth”, on the other the art-historical counter-shot: Portraits of the poor (including a magnificent, effectively staged portrait of a beggar by Luca Giordano) – a, well, very literal form of juxtaposition of rich and poor that leaves one somewhat perplexed.

Lauren Greenfield, Limo Bob, 49, the self-proclaimed "Limo King" in his Chicago office, 2008. Aus der Serie Generation Wealth, 1982?2017. Lauren Greenfield; Foto: Lauren Greenfield

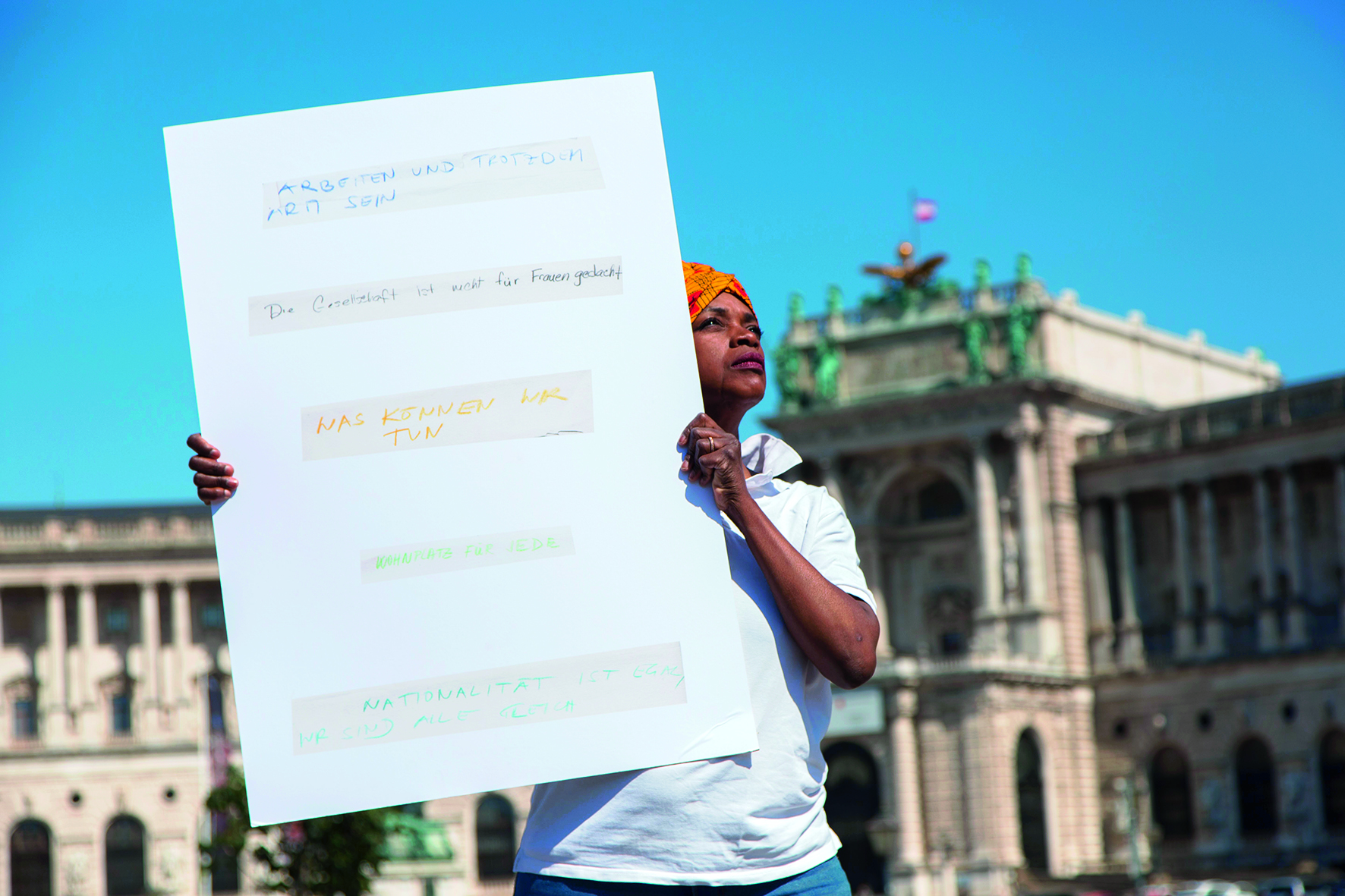

It is gratifying that the exhibition does not stop at art-historical considerations, but also repeatedly illuminates the political potentials (and limits) of art – as a means of agitation, social-critical analysis and the practical fight against inequality (“Critique, Resistance and Protest”). In this context, a series by the Berlin artist duo Alice Creischer and Andreas Siekmann (“An Attitude to Work”) deserves special attention. Using an image system developed by the graphic artist Gerd Arntz and the economist Otto Neurath in the 1920s, Creischer/Siekmann meticulously survey the complex interplay of work, inequality and consumption in seventeen global metropolises (Moscow, Berlin, Rio de Janeiro, etc.) – capitalism critique in infographic format. Didactic, but enlightening.

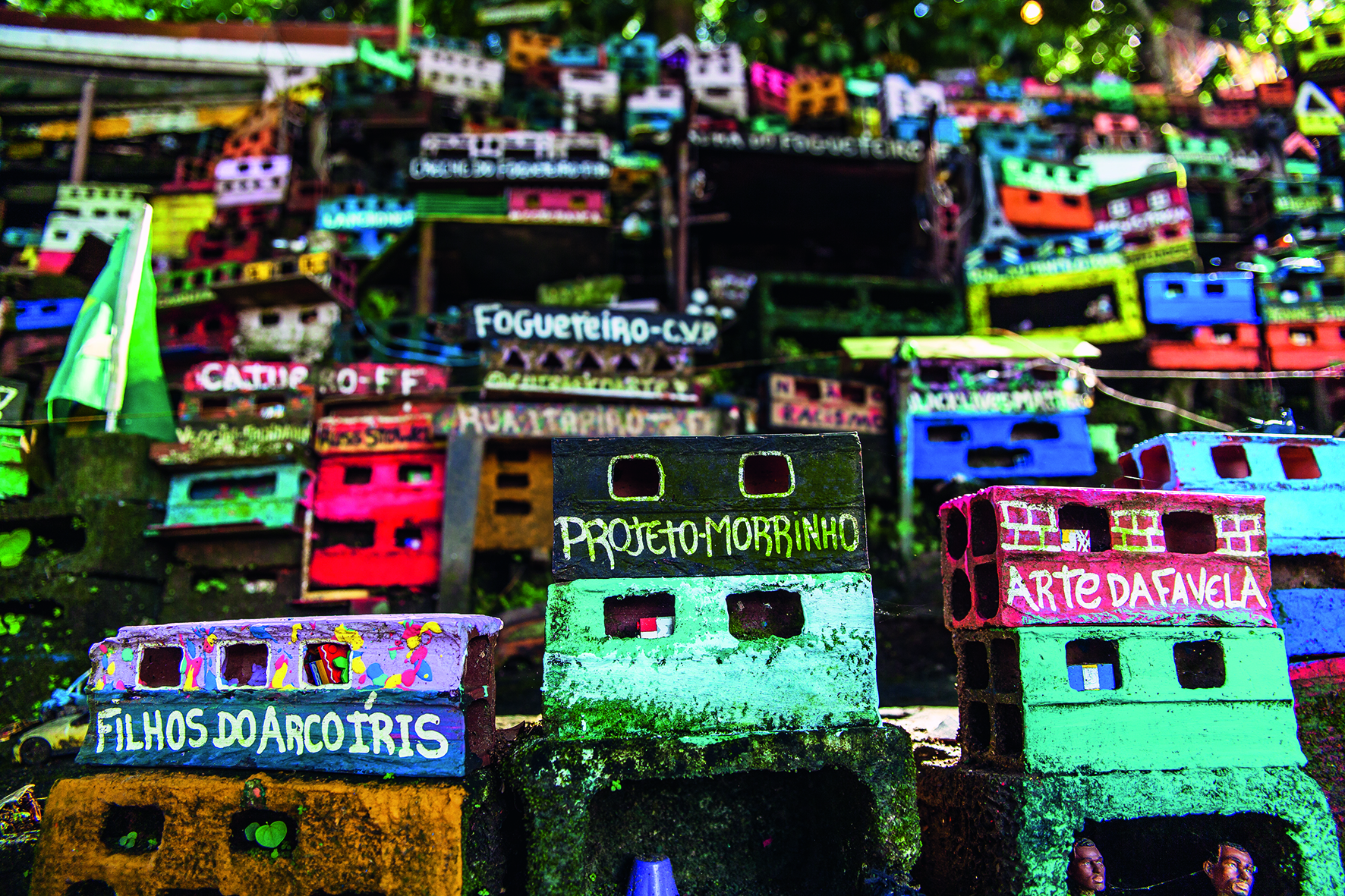

A completely different, not analytical but practical-transformative approach to the topic is offered by the work of the Brazilian artists’ group Projeto Morrinho in the last section of the show (“Places of Inequality”): an installation consisting of a mini-favela constructed of hollow bricks and Lego and a video documentary that provides insights into the work, everyday life and history of the collective. The work produced especially for “Poor & Rich” can be seen as a kind of offshoot of the group’s “parent project”: a miniature replica – now 450m2 in size – of a poor district in Rio de Janeiro, the Pareira da Silva, which has long since become a world-renowned work of art (and popular tourist destination). Poverty as capital? Empowerment has many faces.

Unsurprisingly for a museum of the Archdiocese of Vienna, the Dom Museum is dominated by a charitable view of the distortions between rich and poor. Inequality appears primarily as a distribution problem that, according to the show’s subtext, can be solved by more social engagement – and a more energetic moral engagement of the rich and super-rich. This tendency is only occasionally countered, for example in the works of Iris Andraschek and Isa Rosenberger, who take a more activist position on the problem. The works of Käthe Kollwitz (“The Weavers’ Revolt”), Friedl Dicker Brandeis (“This is what it looks like, my child, this world” – fantastic!) or John Heartfield (“Top Products of Capitalism”) speak a no less clear political language. In them, an insight appears that would certainly also be instructive for current debates on poverty and wealth: the insight that the fight against inequality must not only be about a fairer distribution of resources, but also – and above all – about the rejection of domination. Ilse Aichinger put it this way in a poem about Saint Martin: “Give me the coat, Martin / but first get off the saddle / and leave your sword where it is / give me the whole one.” A demand with explosive power. Fortunately, some of the works in “Poor & Rich” hold fast to it.

(Maximilian Steinborn)