After the intoxication

CRITIC'S PICKS FOR VIENNA ART WEEK:

The loneliness of the satyr. Eleanor Antin, Arian Dean, Jimie Durham, Hamishi Farah, Emilio Prini. Curated by Andrea Bellini.

You know them: the opulent baroque hams by Rubens, Tiepolo and Co. The canvas is full of all kinds of bodies, which ecstatically nestle against some usually rather wine-scented Bacchus. Nymphs, youths and enchanted animals are to be recognized, and, of course, somewhat de-centered, either supporting the no longer quite so steadfast god in the center of the picture, or lying relaxed under some tree in the background of the picture: a satyr. The satyr is many things at once: loyal drinking buddy, cunning trickster, demonic tormentor, embodiment of the joys – but also the ambivalences – of loss of control and ego.

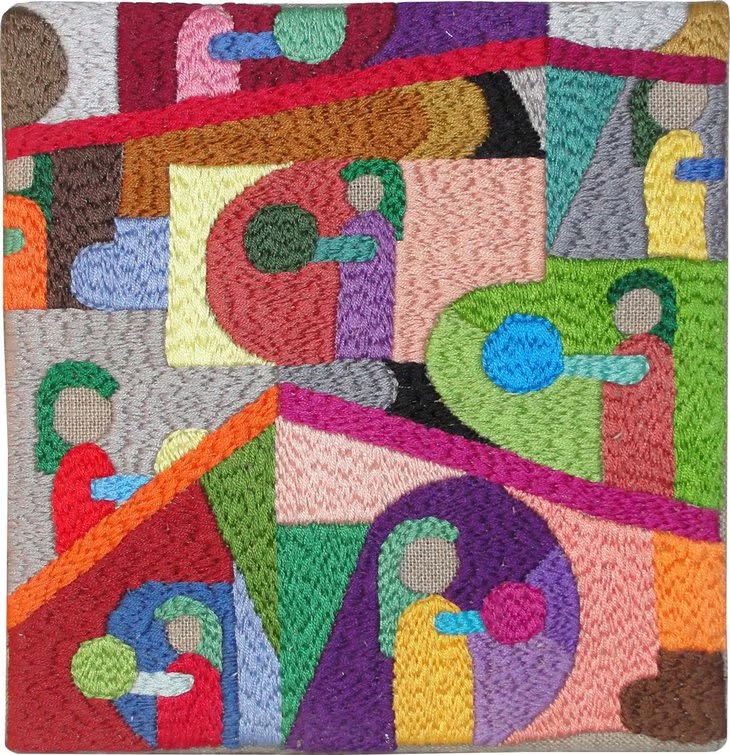

In the current show at Christine König’s “Die Einsamkeit des Satyrs” (The Loneliness of the Satyr), curated by Andrea Bellini as part of curated by, the mythical good-for-nothing, who always seems somewhat enraptured, is above all a metaphor for a method: a way of commenting on things and discourses ‘from the edge’, from a position of non-belonging. The thematic field of the exhibition – identity (loss), ecstasy, the burden (and privilege) of being a subject, etc. – is as diverse as the list of participating artists. On view are works by Eleanor Antin, Arian Dean, Jimmie Durham, Hamishi Farah, and Emilio Prini. Where these positions – so different in terms of background, familiarity, themes, techniques and approaches – (loosely) meet is in the play with gestures of withdrawal, refusal, transformation and travesty.

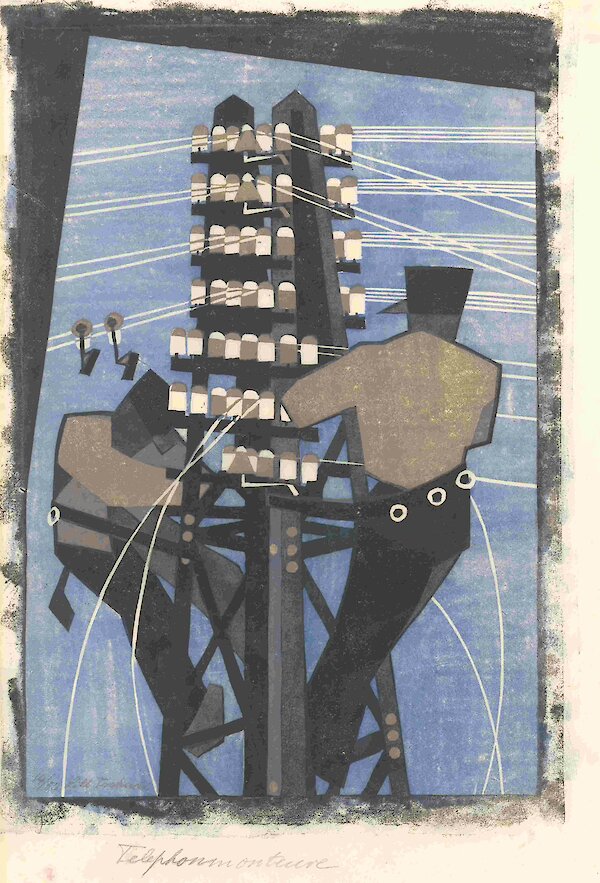

ARIA DEAN Cipher (5), 2021, Courtesy Christine König Galerie, Wien und die Künstlerin Foto: Simon Veres

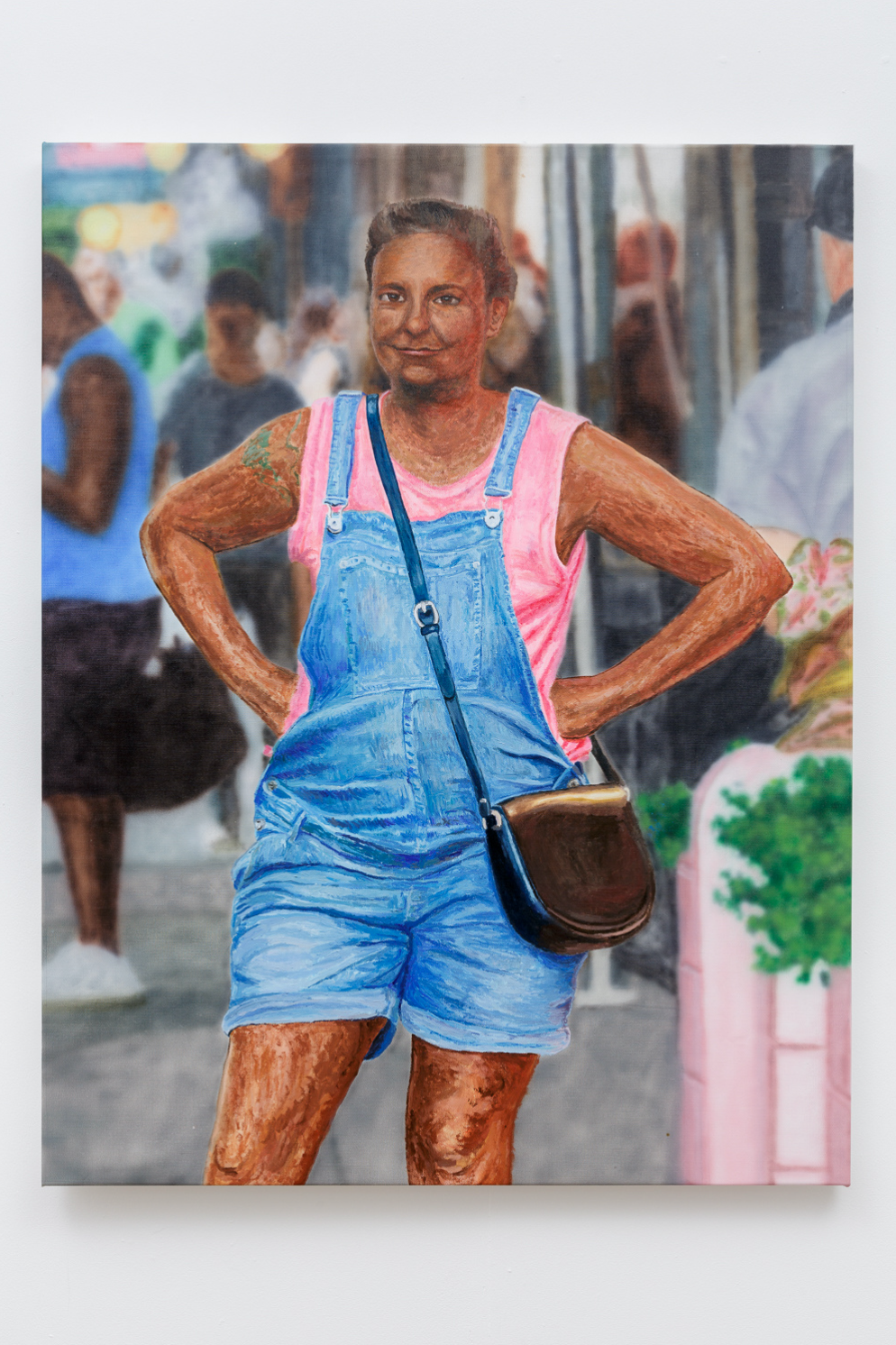

The painter Hamishi Farah begins with an enigmatic portrait of the artist Deborah Joyce Holman (herself a great artist of transformation and refusal). Oscillating between visibility and invisibility, she looks challengingly at us from a pitch-black pictorial space. Right next to it, we encounter a depiction of the titular satyr (the only explicit reference to the exhibition’s title), a floor-to-ceiling wall piece produced by Arian Dean especially for the show, and, likewise, an image of withdrawal: the drawing, it seems, is about to dissolve into the white of the gallery wall. Next to it, in a small baroque mirror, we read a sentence about the ambivalence of intoxication and ecstasy: “She does not die from it, except as a subject.”

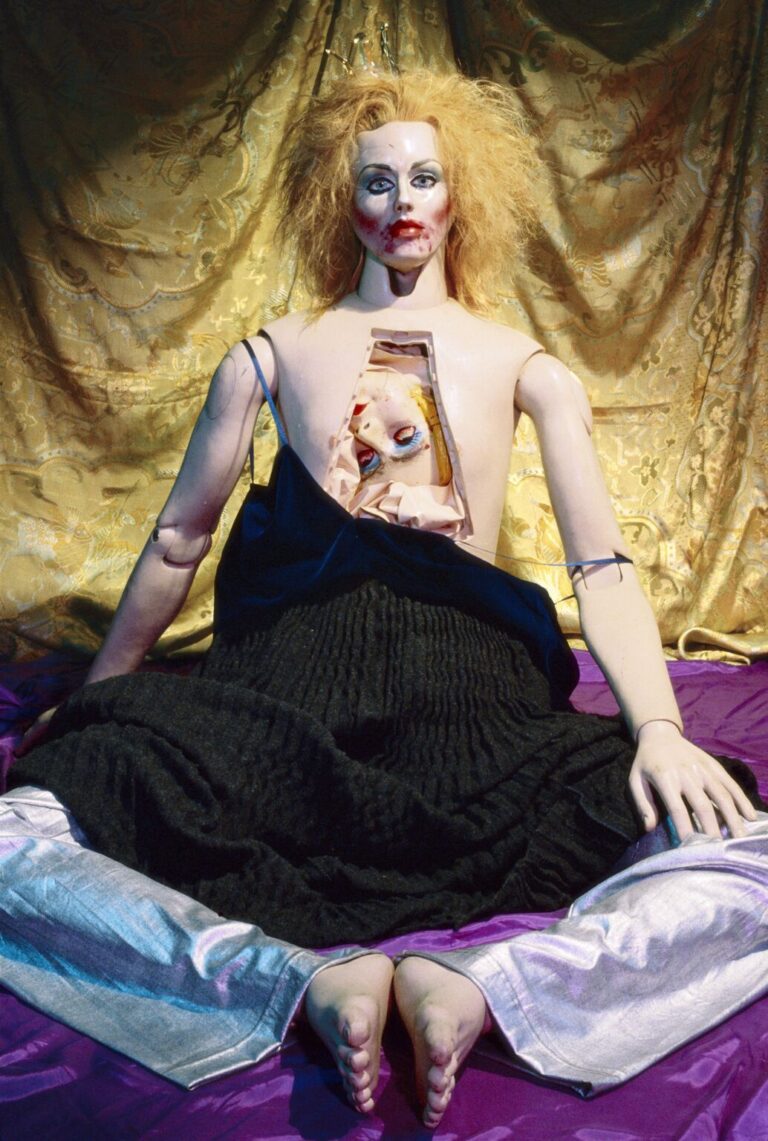

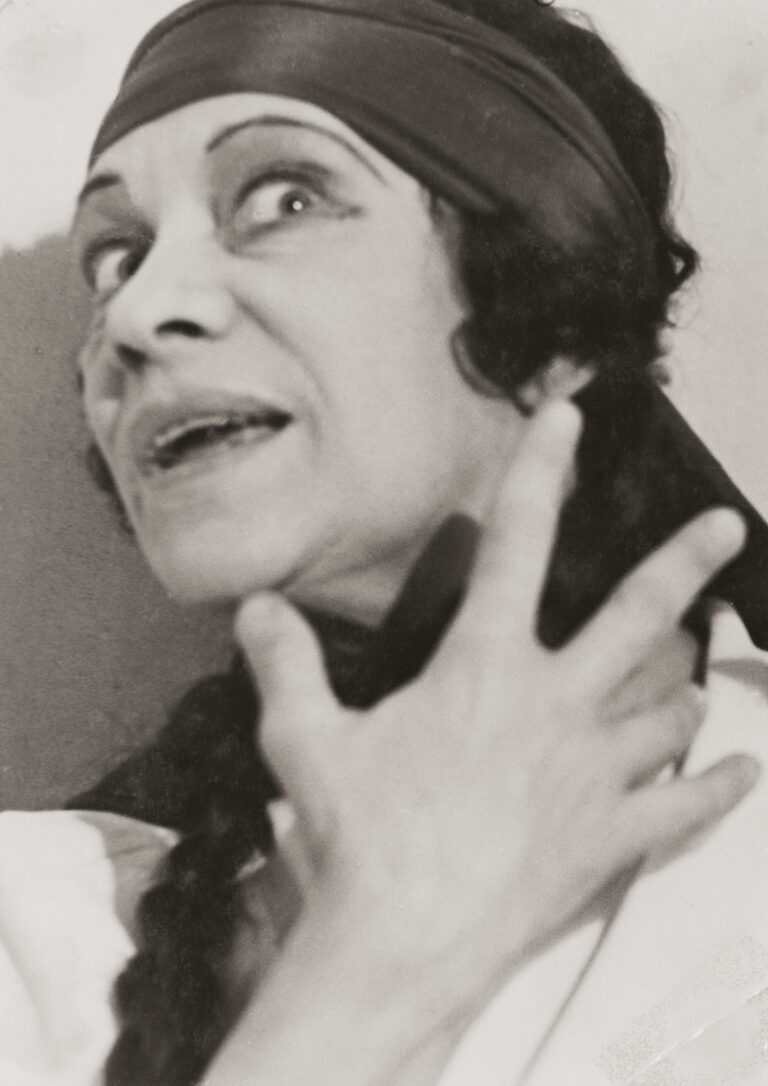

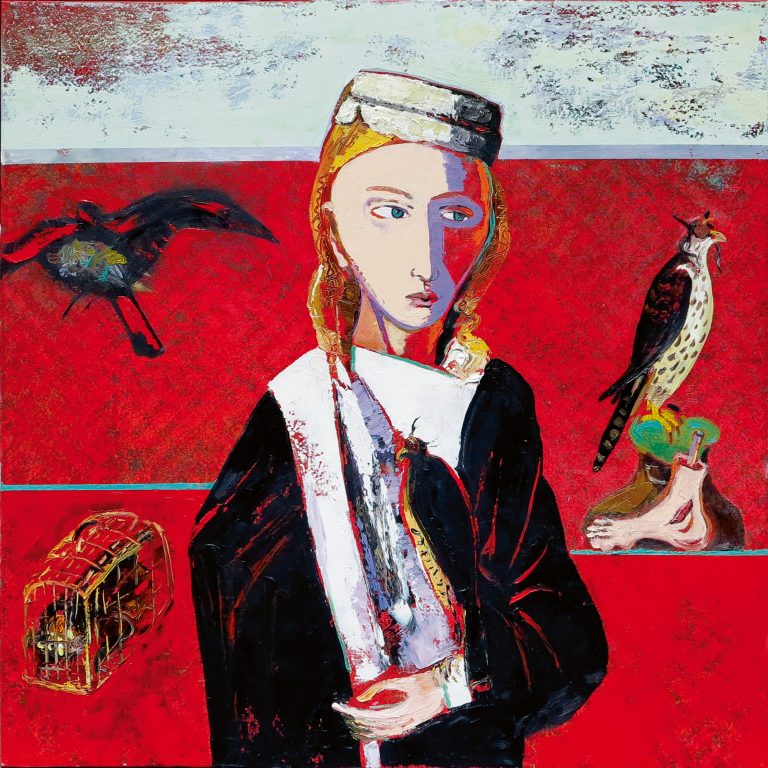

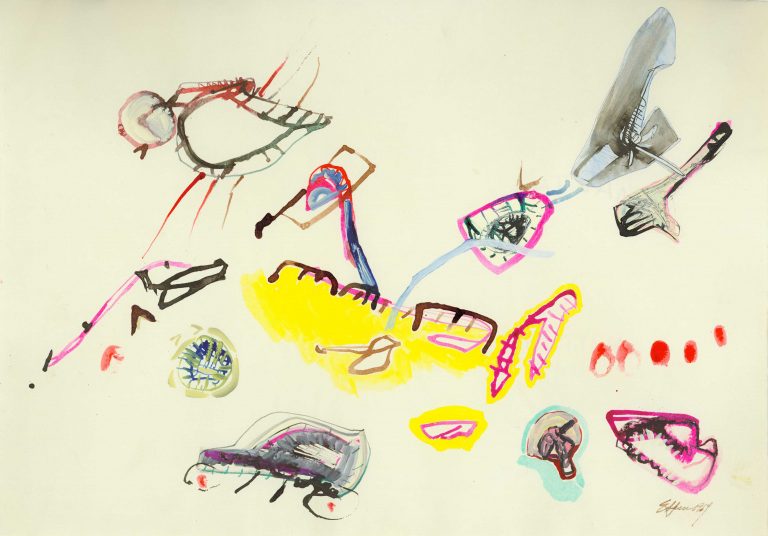

We continue with self-portraits by Eleanor Antin (as a bearded king) and Emilio Prini (as a melancholy clown), the exhibition’s secret highlights: unobtrusive, thoughtful, elegantly balancing pathos and irony. The predicate “satyrical” (should there be such a word) would be appropriate here without a doubt. In contrast, Jimmie Durham’s work “Bruises” on the wall vis-à-vis seems somewhat more casual, a reminiscence of the dark side of the bacchanalian loss of control. We see the artist’s greatly enlarged likeness in sixfold with violent bruises on his eyes and mouth. Durham had allegedly gotten drunk after dental surgery, against medical advice. “Bruises” documents the result. A satyr washed in all waters (and other substances) looks different.

HAMISHI FARAH Black Lena Dunham, 2020, Courtesy Christine König Galerie, Wien und der Künstler Foto: Simon Veres

Those expecting pointed, tightly woven, ‘hefty-baroque’ reference clusters in Bellini’s show will be disappointed. For the most part, the selected works communicate only very loosely with one another. Some – especially Farah’s – works seem almost a bit arbitrary in the setting (though, strong in their own right). Still, “The Loneliness of the Satyr” is a treasure trove. The mythical reveler may not find himself among his peers everywhere in the show. But he would certainly not be lonely in it.

(Maximilian Steinborn)