Long unrecognized, now appreciated – Gabriele Münter at the Leopold Museum

"In many people's eyes, I was an unnecessary addition to Kandinsky". This statement opens the major retrospective of this long misunderstood artist at the Leopold Museum. A text by Sabine B. Vogel.

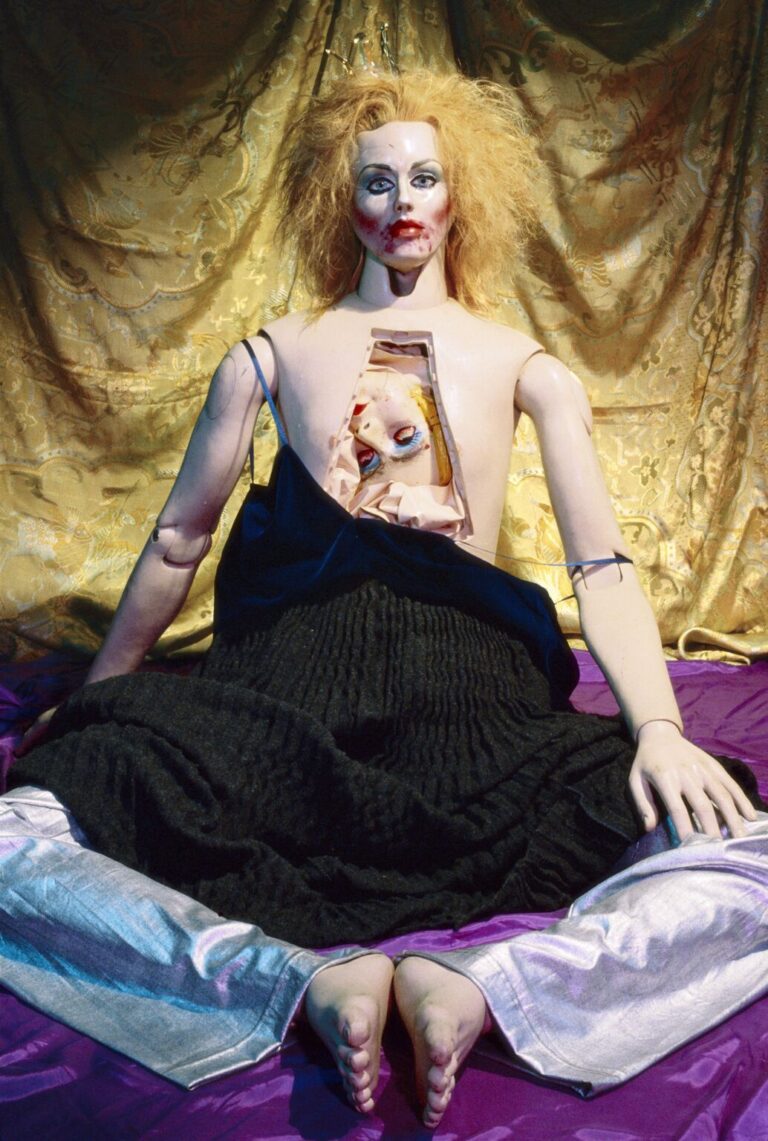

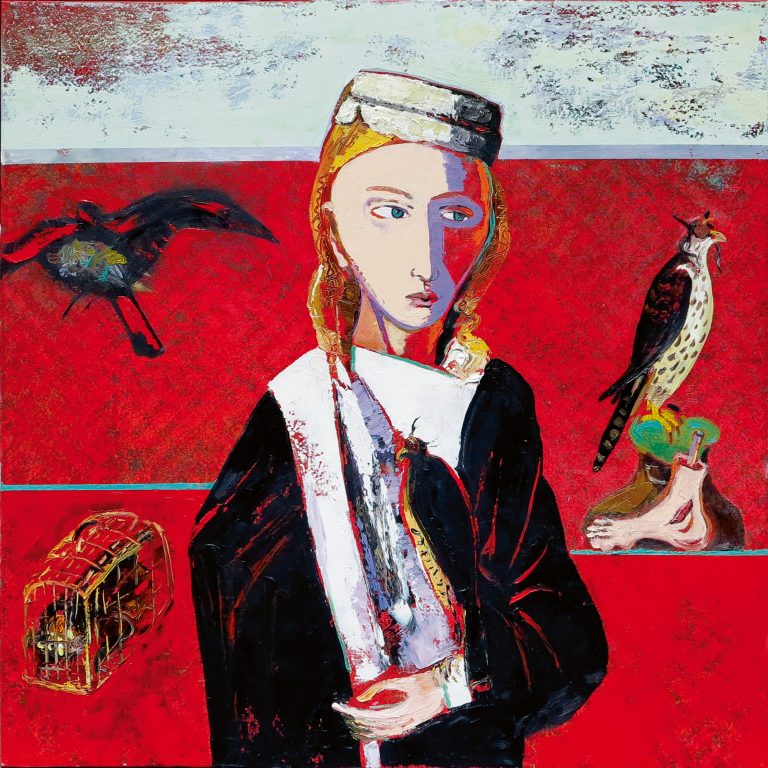

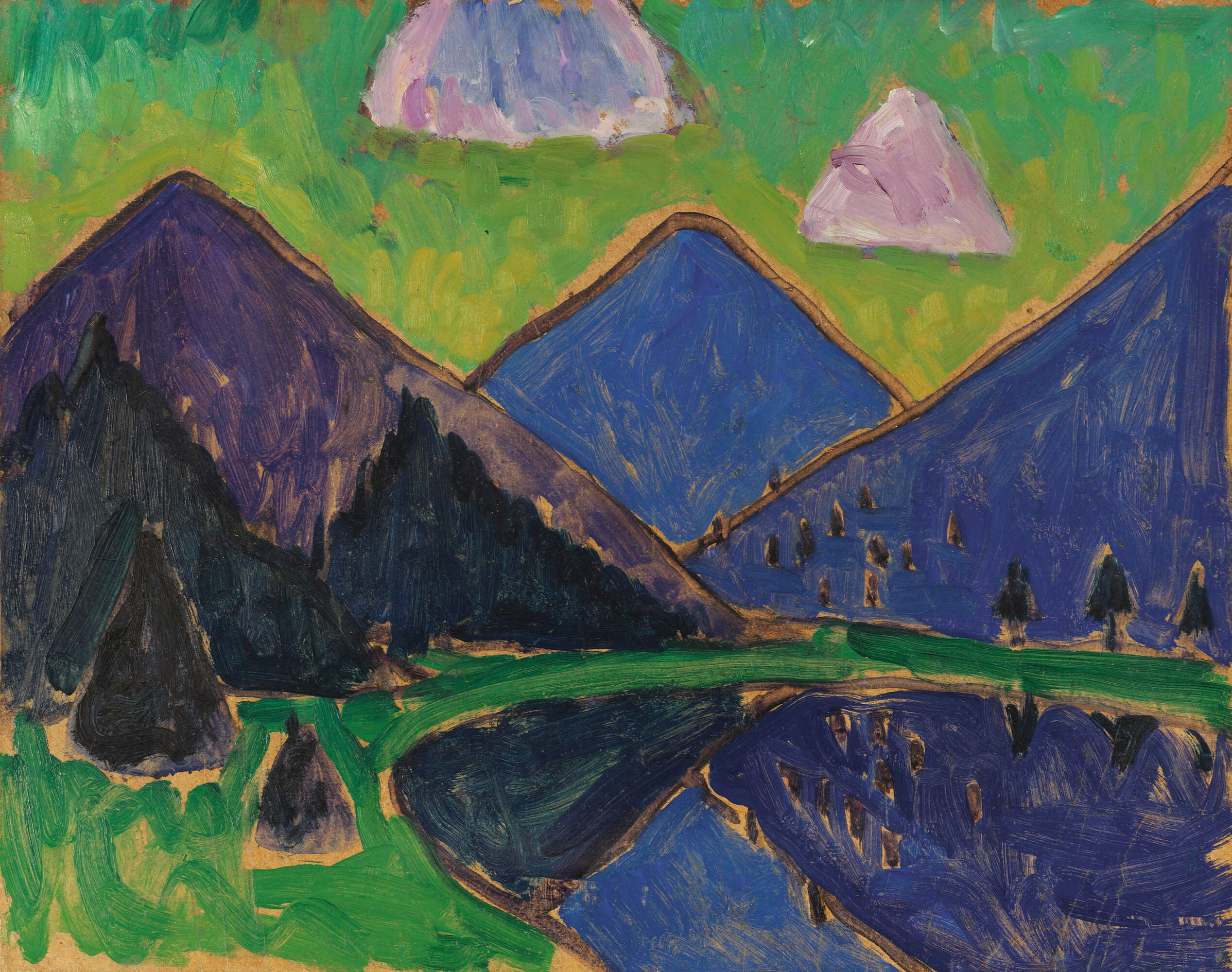

GABRIELE MÜNTER, The blue lake, 1954, Photo: LENTOS Kunstmuseum Linz/Reinhard Haider © Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

The diaries in which Gabriele Münter collected her thoughts were barely three centimetres in size. In 1926, she noted: “In many people’s eyes, I was an unnecessary addition to Kandinsky”. This statement now marks the beginning of the major retrospective of this long misunderstood artist at the Leopold Museum. Around 140 exhibits set the record of art history straight, which for a long time only accorded the painter a biographically motivated marginal position: born in Berlin in 1877 into a wealthy family, Münter repeatedly took private lessons from painters and in ‘ladies’ academies’ from 1897 onwards – at that time, women were denied access to art academies. In 1901, she moved to Munich and took courses in nude drawing and painting with Wassily Kandinsky at the “Phalanx” painting school. She became his lover. Due to the war, the Russian-born painter had to leave Germany after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914 and they went to Switzerland together. Münter moved to Stockholm in 1915 and Kandinsky moved to Moscow in 1916. Münter saw her lover again briefly in 1917 before he finally cut off contact. Years later, she learned that he had married the much younger Nina Andreevskaya in 1917.

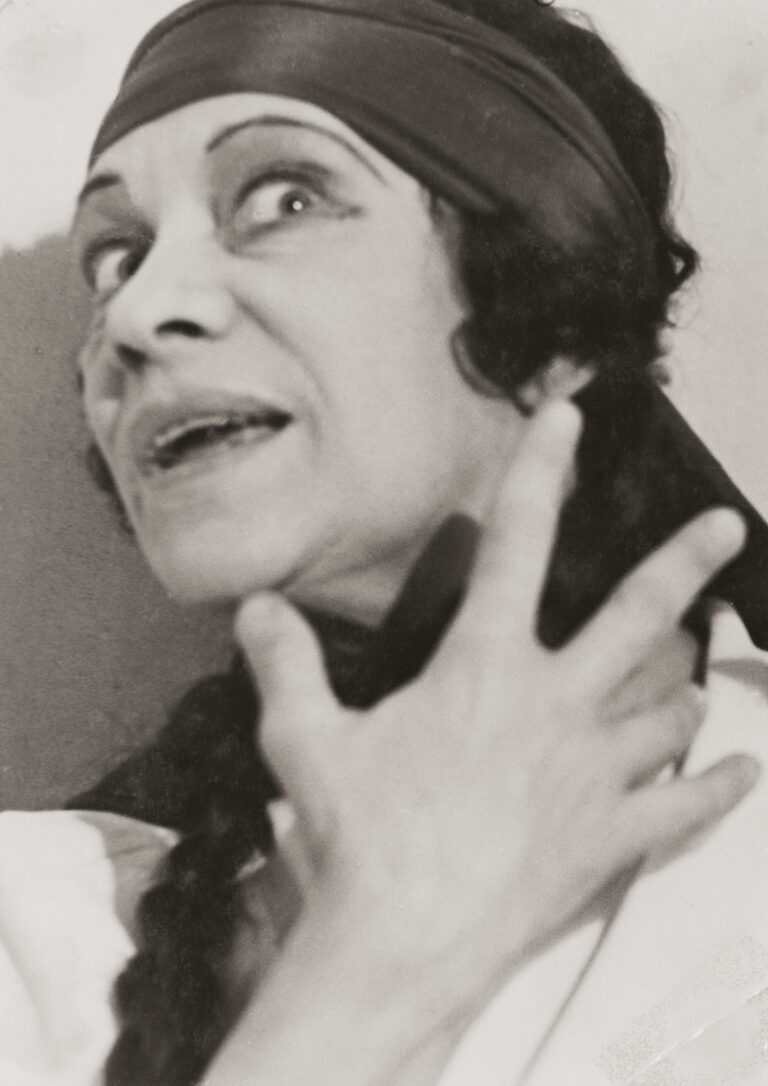

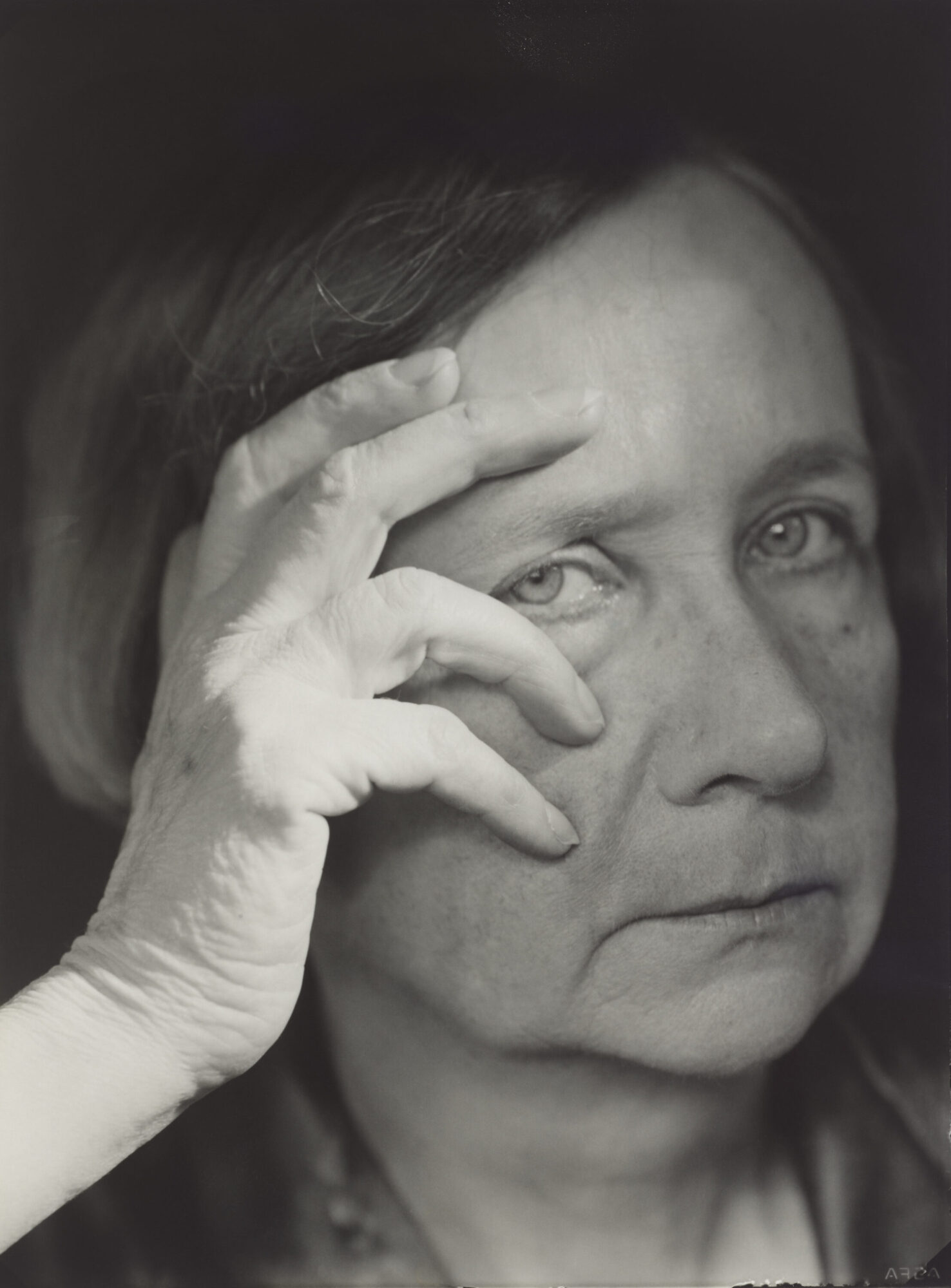

ANONYMOUS PHOTOGRAPHER, Gabriele Münter, around 1935, Photo: Gabriele Münter and Johannes Eichner Foundation, Munich © Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

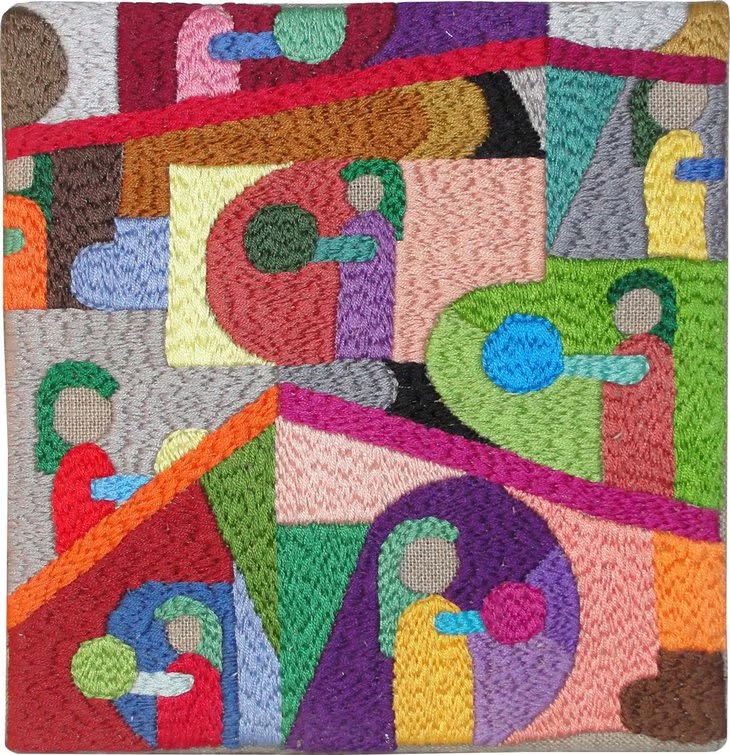

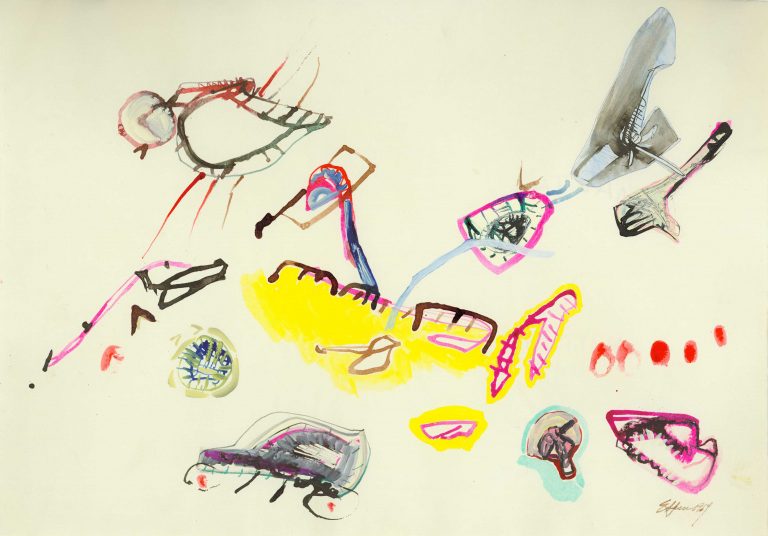

In the twelve “themed islands” in the Leopold Museum, Münter’s works are linked to information about her life. Her paintings, however, do not reflect the sometimes traumatic moments of her life. Her early works are classified as Expressionist, the colors are strong, the motifs of the still lifes and landscapes reduced. Unlike her lover, she tried her hand at radical abstraction, but always remained attached to representationalism – sometimes almost to the point of naïve painting.

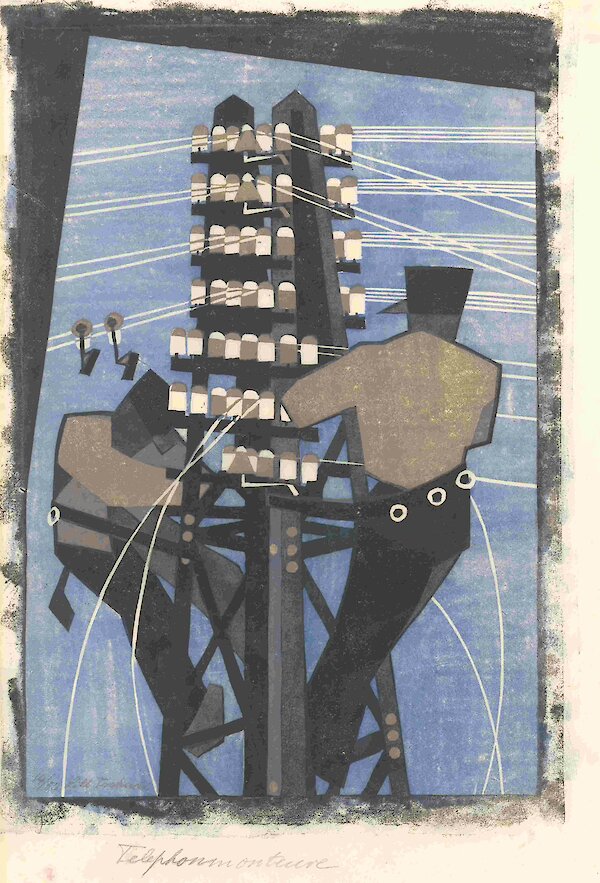

GABRIELE MÜNTER, View of the Murnauer Moos (Blue Mountains), around 1910, Photo: Ketterer Kunst GmbH und Co. KG © Bildrecht, Vienna 2023

At the same time as Münter’s retrospective, the Leopold Museum is also showing a Max Oppenheimer retrospective with a focus on portraits – what a difference to Münter’s portraits! Oppenheimer’s works are characterized by strong emotions; in the depiction of the hands alone – inspired by Schiele – Oppenheimer gives an expression of struggle and despair. In Münter’s works, on the other hand, an intact world prevails even in those later works that belong to the New Objectivity movement – perhaps because she was a “reserved person”, as the Arte portrait says? The Leopold retrospective gives no indication of this, but one thing becomes clear here: the artist’s great strength lay in her uncompromising independence. At a time when art was determined by a clear canon, when artistic success was closely linked to belonging to styles and schools, Münter always remained connected to her very own visual language.