I sing against Monsanto

"And if I devoted my life to one of its feathers?" at Kunsthalle Wien in cooperation with Wiener Festwochen

Curated by Miguel A. López

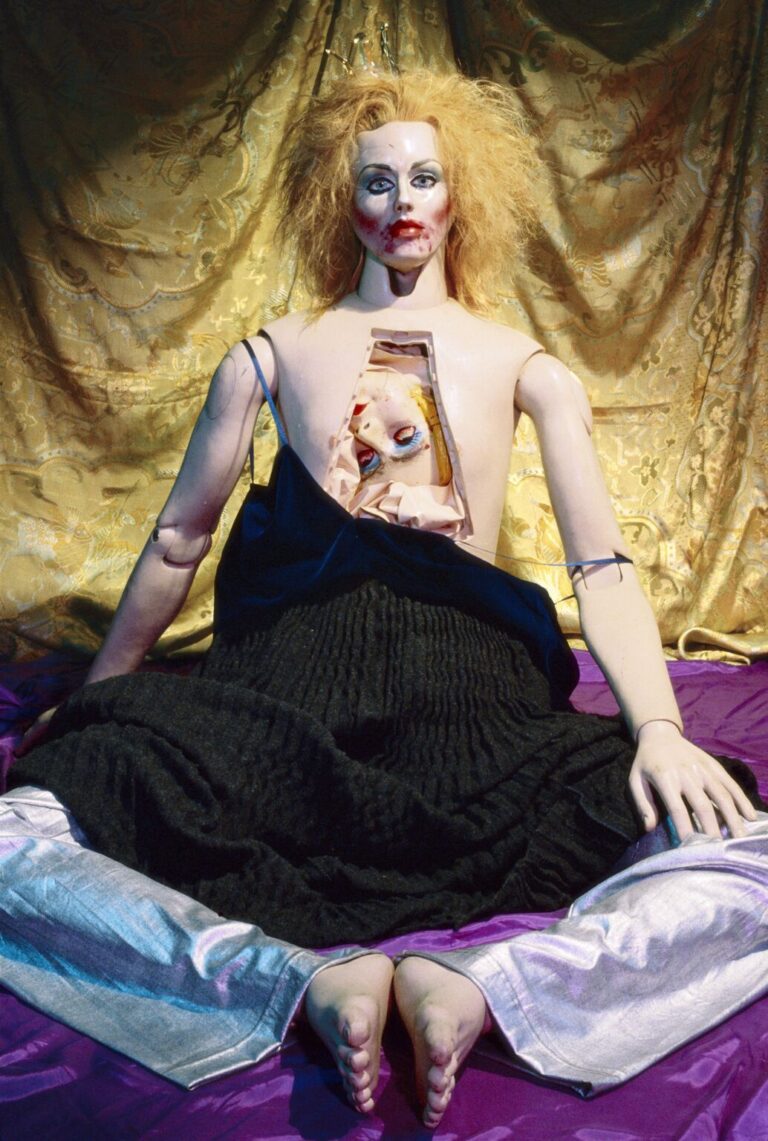

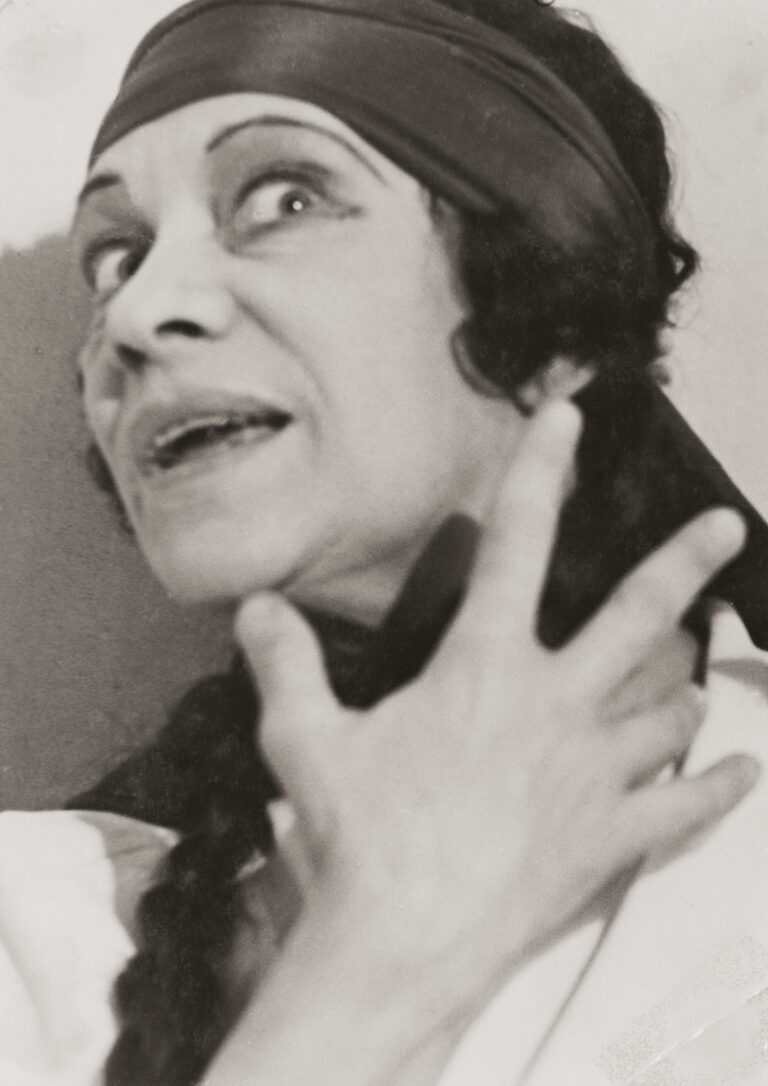

Germain Machuca, Las dos Fridas / Sangre Semen / Línea de vida [Die zwei Fridas / Blut Samen / Lebenslinie], 2013, Foto: Claudia Alva, Courtesy der Künstler und Museo de Arte de Lima

If you only have a short time to see this exhibition, it is advisable to start in the basement of the Kunsthalle Wien. Firstly, you might miss this part – and that would be a pity – and secondly, it offers a good introduction to the show, which is not exactly lacking in addressing topics and issues, with strong works.

I start with the hypnotic film “Mermaids, Mirror, Worlds”, a two-channel film installation by Australia’s Karrabing Film Collective from 2018. The meandering narrative uses a fiction about child abduction to virtuously and poignantly address the sinister consequences of environmental contamination caused by global mining companies. The 26-part “Abc of Racist Europe” by Peruvian artist Daniela Ortiz presents an alphabet of the unequal realities of migrant and indigenous population groups vis-à-vis a “white supremacy”: T for Tourist, for example, lists the free travel of privileged classes against thousands of forced migrations. And in the same room, two tapestries by Olinda Silvano / Reshinjabe, entitled “The Spirit of the Mother Plants”, praise the power of traditional indigenous herbal medicine, which here has also helped against a Covid 19 disease.

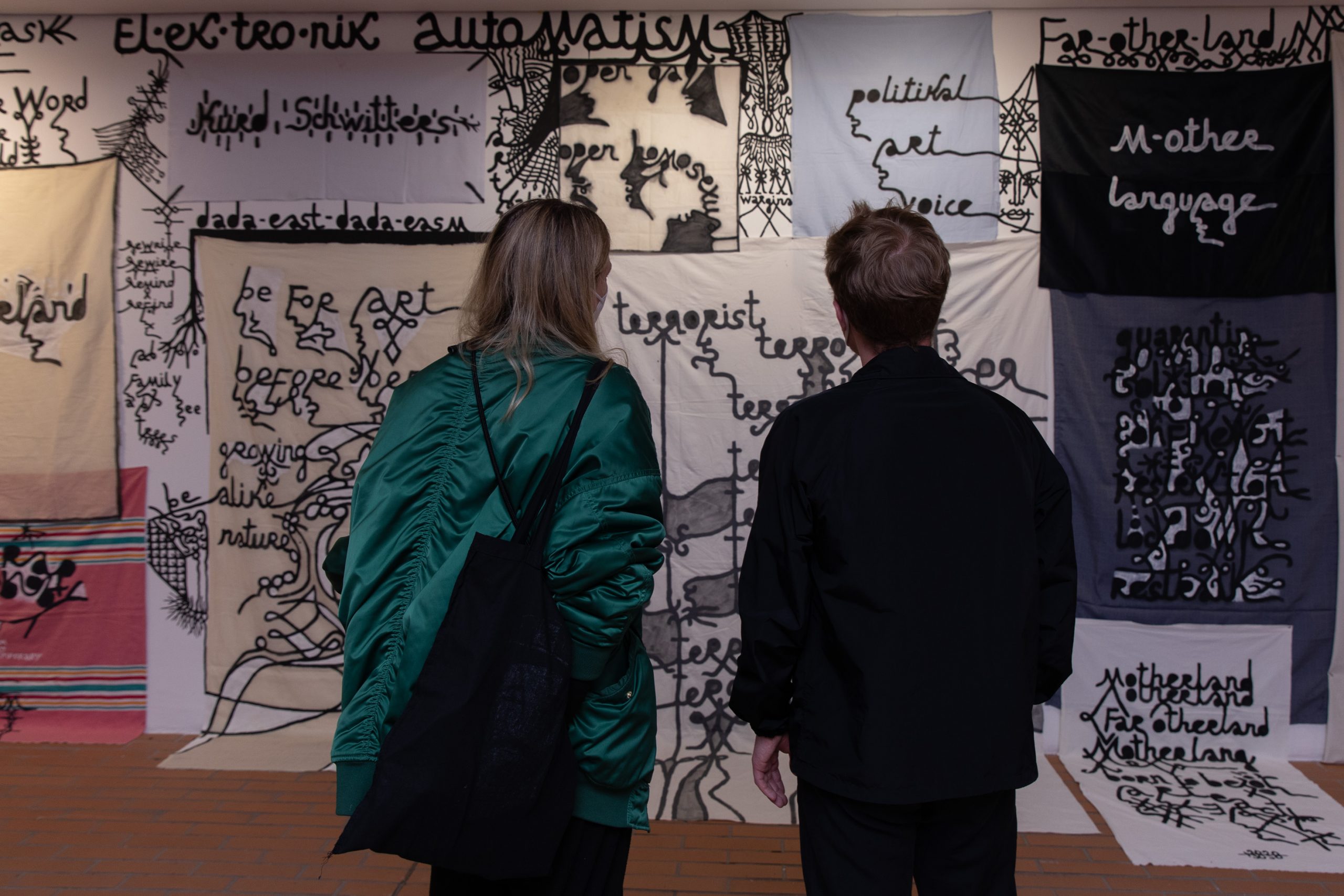

Babi Bdalov, m-Otherlanguage, 2018

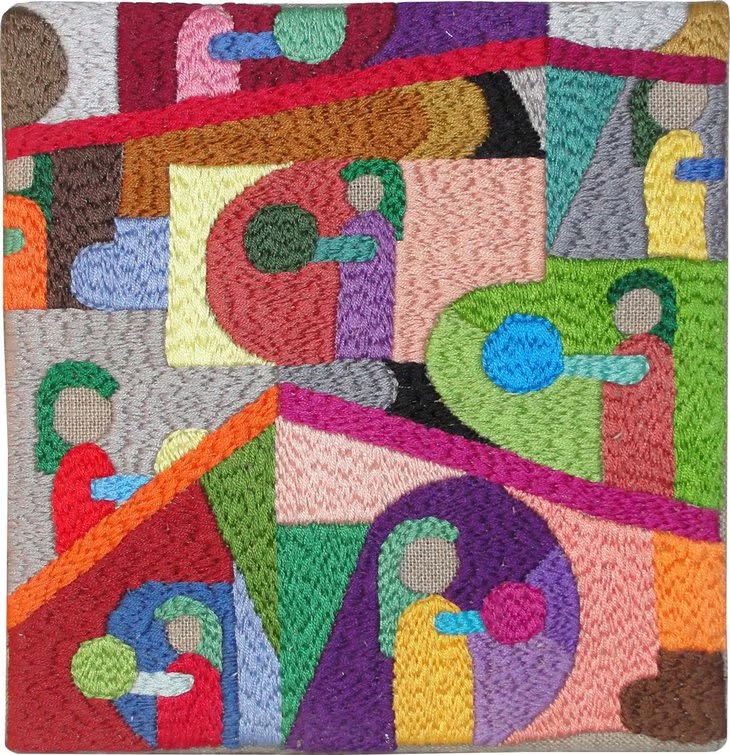

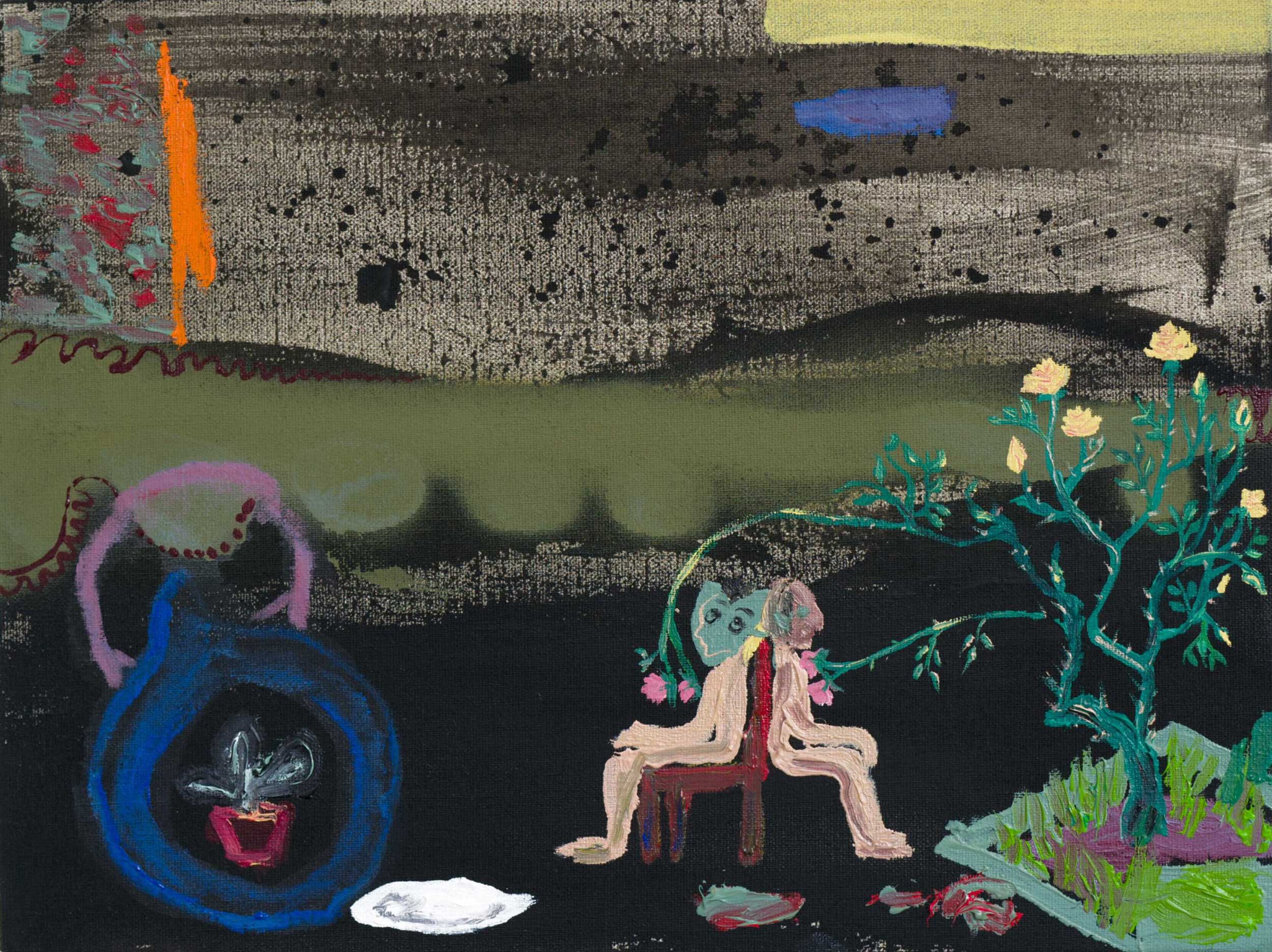

Nilbar Güreş, Breasts by Rose, 2020, Courtesy die Künstlerin und GALERIST, Istanbul, Foto: Reha Arcan

Poetically titled “And if I devoted my life to one of its feathers?”, this year’s Festwochen-exhibition diagnoses our present against the backdrop of global power conglomerates, environmental destruction and social injustice. Originally planned for 2020 by Peruvian curator Miguel A. López, its initial situation must now prove itself under the conditions of a world with and post Corona.

The works of the approximately 35 artists and groups positively revolve around notions of collectivity in – not only, but predominantly – postcolonial territories. Indigenous traditions are resumed despite or against the social devastation caused by the consequences of colonialism and the seamless transition to hegemonic, exploitative economic conglomerates. The cementing backbone of these structures is almost exclusively a patriarchy that is still effective. In summary, these are the theses of the exhibition, which are expressed not only through different cultures but also through their different artistic approaches.

Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids, Mirror Worlds, Filmstill, 2018

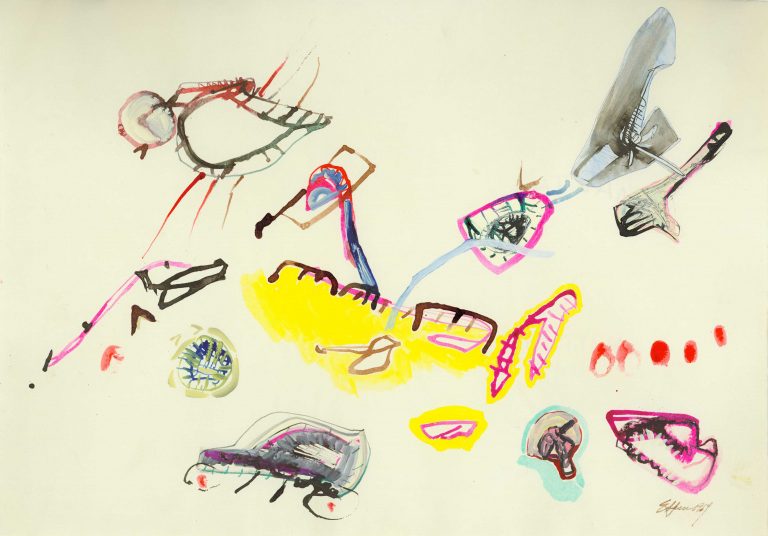

Amoako Boafo, Gold Plant, aus der Serie Detoxing Masculinity, 2017 © Bildrecht Wien, 2021

What can be grasped together in the basement in terms of content and through the concentration on the themes of postcolonialism, critique of capitalism and indigeneity, on the other hand, becomes increasingly blurred in the main hall on the upper floor, which is difficult to manoeuvre. Here we are confronted with impressive works, but the partly unmotivated hanging as well as the inclusion of artistic positions that are interesting in their own right but seem to have been brought in mainly to establish a local reference, the theme becomes too broad. The excessive diversity of nations and conflicts gives rise to an arbitrary cartography of global mechanisms of oppression that is counterproductive to the virulent theme. And if a “local” focus has already been the driving force, why not take positions that also deal with the specific problems of Latin America, such as the works of the Austrian artists Ines Doujak or Oliver Ressler? Moreover – and this is perhaps the most important point – a contextualisation and a mediation of the works is missing, especially in their aesthetic choices. For the deliberately chosen means, which oscillate between naïve painting, folk art, indigenous and autochthonous techniques, in turn belong to a realm of very specific ways of being, characterised by their own language, their own materialities and their own meanings. One wishes these had been conveyed more thoroughly.

But one should not be put off by the fuzzy context. Great works such as Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe’s “affective” plant directory of trees that provide fruit to eat or Manuel Chavajay’s drawings combining cosmovisions and knowledge from Mayan spirituality can be discovered. These are works that oppose the often depressing content with associative ramifications and playfulness in a poetic and heroic way. This also includes performance and video works such as those by Bartolina Xixa or Amanda Piña: here, too, cheerful-looking overformations such as carnivalesque idioms were chosen in order not to dully reproduce colonialist power relations, but to make them tangible through their own practices of resistance. As Bartolina Xixa puts it in “Ramita Seca. La Colonialidad Permanente”, dancing on a rubbish dump in the Andes? “I sing against Monsanto.

Karrabing Film Collective, Mermaids, Mirror Worlds, Filmstill, 2018