FACING TIME

For its 20th edition, VIENNA ART WEEK 2024 is approaching the phenomenon of time from different angles with its motto.

By Robert Punkenhofer & Julia Hartmann

Every year in November, VIENNA ART WEEK celebrates the Viennese art scene. In 2024, with the 20th edition of the festival, we take a moment to recapitulate the past, understand the present, and anticipate the future of a visual arts festival that brings Vienna’s major institutions, artists, cultural practitioners, theorists, galleries, independent art spaces, philosophers, and an inter/national audience under one roof. With “Facing Time” as this year’s theme, the VIENNA ART WEEK reflects on its own almost 20-year history while exploring the profound dimensions of Time itself.

Time affects everyone, and trying to visualize its essence is as challenging as capturing its fleeting nature. In that sense, the ancient Greeks offer one of the earliest insights into this challenge through the concepts of chronos and kairos. Whereas chronos embodies the linear and chronological aspect of time, kairos represents the opportune and qualitative dimension, urging us to recognize and seize the right moments in life—or, as the Romans would say: carpe diem. While our modern lives are conventionally structured by linear time, meticulously measured by clocks, our ancestors and some contemporary cultures adhere to a different, more cyclical and rhythmic understanding of temporality by measuring the passage of time in recurring cycles known as “circadian time.” This rhythm, or rather our body’s internal biological clock, plays an important role in regulating various functions such as sleep, hormones, and metabolism, and is crucial for maintaining overall health and well-being; we are all familiar with the disorienting feeling of having our “internal clock” disrupted by jet lag or daylight saving time adjustments. Conversely, calendars that represent time as a chronological concept are a relatively recent phenomenon. And yet when this conventional way of measuring time is disrupted, we often anticipate the “end of the world,” as happened before the early 2000s (Y2K) or when the Mayan calendar seemed to end in 2012. The understanding of time becomes even more complex with a deeper look at the personal side of aging and mortality, which can often give rise to feelings of nostalgia, retrospection, vanity, and chronophobia—more commonly known as a “midlife crisis.”

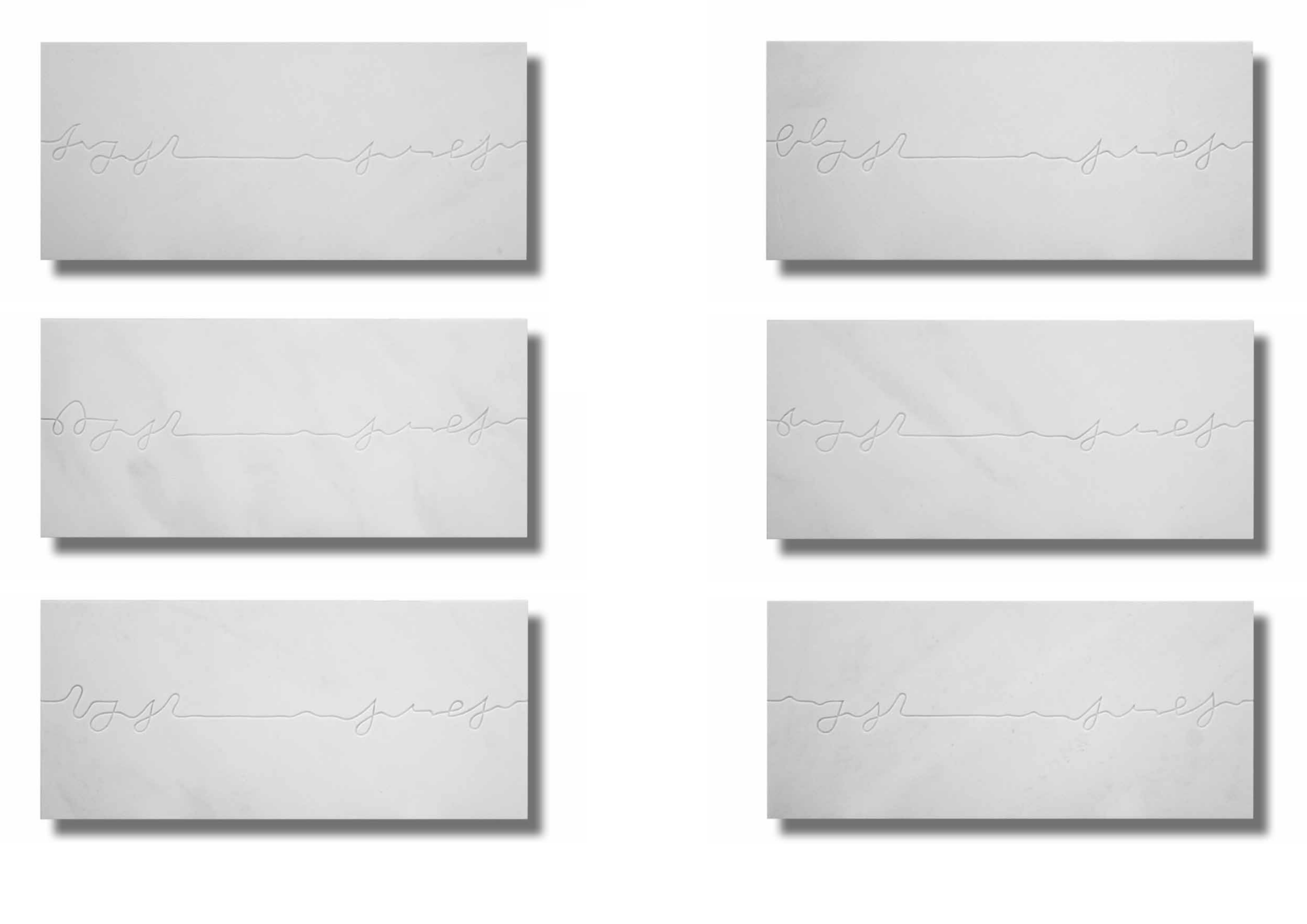

From an art-historical perspective, artists have for centuries employed symbols and allegorical elements to convey the passage of time, such as hourglasses, skulls, wilted flowers, and clocks. The concept of memento mori has also served as a poignant reminder of the transience of life and the inevitability of death, as in Renaissance paintings exploring this theme with depictions of the three different ages of man. In Salvador Dalí’s “Persistence of Memory” (1931), clocks appear melted and softened, offering an interpretation of the fleeting nature of time or perhaps a call to appreciate the present moment. In a more contemporary work titled “within a second,” Arnold Reinthaler examined the smallest chronological unit of time used in everyday life, the second. Across a series of panels, Reinthaler translated a second of digital time into shorthand and engraved it into marble. In visualizing time through the hard material of the stone (a performative act that takes longer than a second to implement) the artist deconstructs the conventional counting of time, thereby reminding us that time is relative.

Arnold Reinthaler, within a second. Since 2007, series, engraving in white marble, each 100 x 45 x 2 cm. Exhibition view 'time offset - phase signatures', dreizehnzwei, Vienna, 2007.

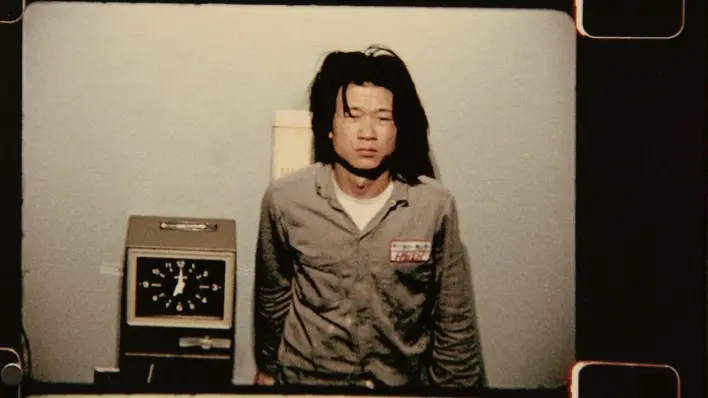

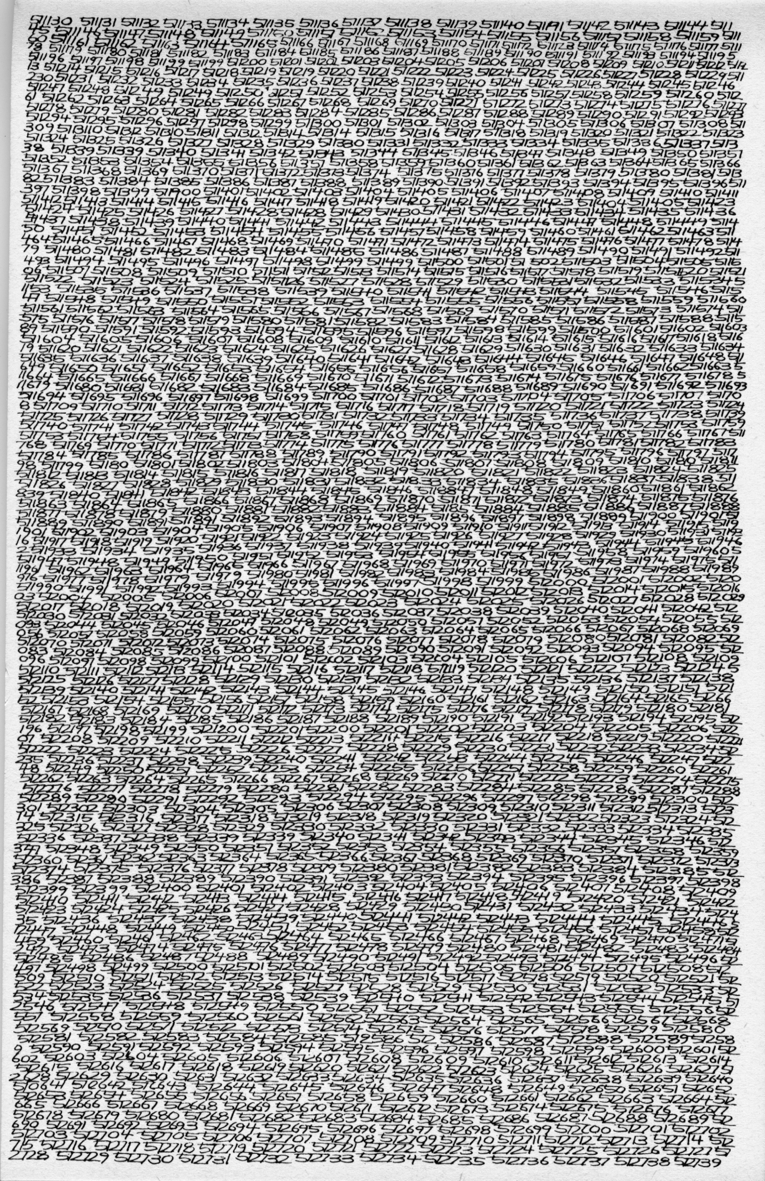

The advent of photography granted artists the ability to freeze time, or chronos, on paper. Eadweard Muybridge’s serial photographs stand as a crucial example of early attempts to capture fleeting moments that eventually evolved into moving images. Recent decades have seen time-based art forms such as video, performance, film, installation, and sound art become popular means of expressing duration and endurance. Iconic works in this category include Andy Warhol’s real-time film “Empire” (1965), an eight-hour single shot of the Empire State Building, or Christian Marclay’s video work “The Clock” (2010). The latter is a 24-hour-long montage consisting of thousands of movie and television images of clocks, edited together to show the actual time. Similarly, in “Time Clock Piece,” Taiwanese artist Tehching Hsieh sought to immortalize the passage of time by monotonously punching a worker’s time clock every hour, day and night, from 11 April 1980 to 11 April 1981. Dressed in a worker’s uniform, Hsieh addressed his status as an illegal immigrant in New York City and critically compared the time spent in his studio to the monotony of shift work. In “OPALKA 1965/1 – ∞,” painter Roman Opałka took the visualization of time to a whole new level by attempting to count to infinity: starting in 1965, he drew numbers on canvas every day until his death in 2011, manifesting the incessant passage of time while at the same time confronting his own mortality (and the necessary impossibility of his endeavor). Similarly, On Kawara documented time by consistently painting the date of each day after 4 January 1966 on canvas, adding to the back newspaper clippings from that day. Kawara would eventually create thousands of “Date Paintings,” which only ended with his death in 2014. Anna Jermolaewa’s wall installation “Clockwork” (2021), on the other hand, visualizes time by using train station clocks from Austria, the former GDR, the Czech Republic, and the Soviet Union that stopped at the time they were severed from their “master clock.” Although the clocks are obsolete, they mark a moment in history that represents the failed political systems from which they came.

While the above-mentioned artists approached their work in terms of linear time and duration, others such as John Cage, Yayoi Kusama and Katie Paterson have sought to visualize more abstract concepts such as infinity, coincidence, and chance—in other words, what the ancient Greeks called kairos. Fascinated with ideas of endlessness, Kusama makes “Infinity Mirrored Rooms” that transcend time and space and create the illusion of infinity. Katie Paterson experimented with the space/time continuum in a slightly different way by filling an hourglass with stardust—the fossilized remnants of a time before our planet even formed—that had traveled to Earth over millions of years. Cage approached the concept of time through his art by using uncertainty and chance to determine the duration of his musical pieces.

In today’s world, time is considered a commodity, a valuable resource—who hasn’t used the phrase “time is money”? On the one hand, the aphorism highlights the idea that time can be spent, saved, invested, or wasted, and emphasizes its scarcity and thus luxury; which, on the other hand, is a growing socio-economic and feminist issue in the work place. A recent statistic shows that in Austria almost 80 percent of the part-time jobs are held by women, mostly due to caregiving commitments. This often results in a double burden for women, who earn less money for much more of the workload. Faith Wilding explored this issue as early as 1972 in the form of a 15-minute monolog. The artist condensed a woman’s entire life into a monotonous, repetitive cycle of waiting for life to begin while serving and sustaining the lives of others. In one passage, Wilding reads: “Waiting for some time to myself. Waiting to be beautiful again. Waiting for my child to go to school. Waiting for life to begin again. Waiting …”

Faith Wilding, Waiting (1972). Video still. Source: https://vimeo.com/36646228

In a sense, waiting, spare time, and a “work-life balance” have become luxuries in today’s society. German sociologist Hartmut Rosa theorizes on this issue with the idea of “social acceleration,” which refers to the perceived increase in the pace of life that affects our perception of time. He suggests that, as our modern lives accelerate, we may feel a sense of time pressure and experience a dissonance between the speed of societal developments and our ability to adapt. Here, Rosa introduces the concept of “resonance” as a potential counterforce to the alienating effects of acceleration. He refers to experiences that are deep, meaningful, and fulfilling. Finding resonance becomes crucial as a way to counteract the negative effects of a fast-paced society. “Time poverty” or “time scarcity” are also issues that Teresa Bücker critiques in her book Alle_Zeit. Eine Frage von Macht und Freiheit (All_time: A question of power and freedom). Bücker calls for political and social changes that grant the right to spare time, “as spare time is a human right.”

Ultimately, this year’s VIENNA ART WEEK aims to face the passing of time head-on and encourage its visitors to take the time to enjoy art and the present moment itself. Not least because the 20-year, uninterrupted continuation of a non-profit festival is certainly cause for celebration. It’s time to celebrate!