Emília Rigová’s islands of well-being at MUMOK

In her solo show "Nane Oda Lavutaris/Who Will Play for Me?" at MUMOK, the Slovak artist Emília Rigová takes up the theme of Roma and music. A text by Sabine B. Vogel.

“Gypsy boy, where are you, where are your songs” sang the German pop singer Alexandra in 1968. The hit was a romantic transfiguration of the Roma. But the song is also true in one respect: the meaning of music for Roma. In her solo show “Nane Oda Lavutaris/Who Will Play for Me?” at MUMOK, Slovak artist Emília Rigová now takes up this theme.

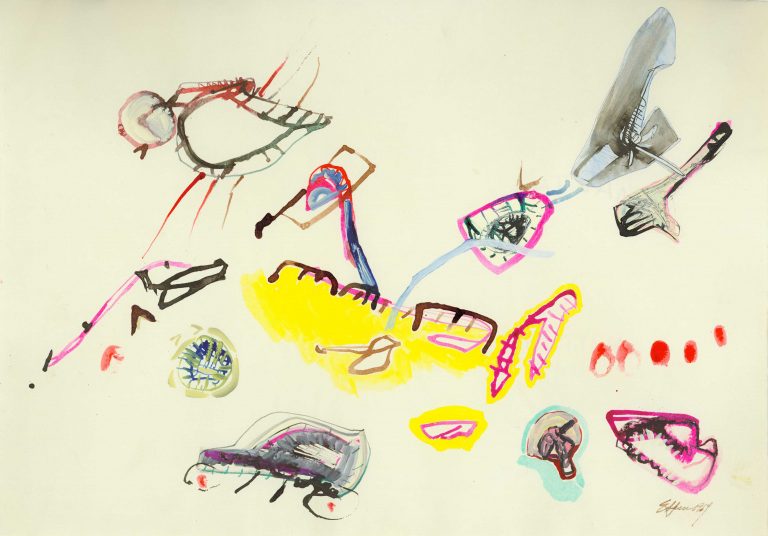

© Emília Rigová

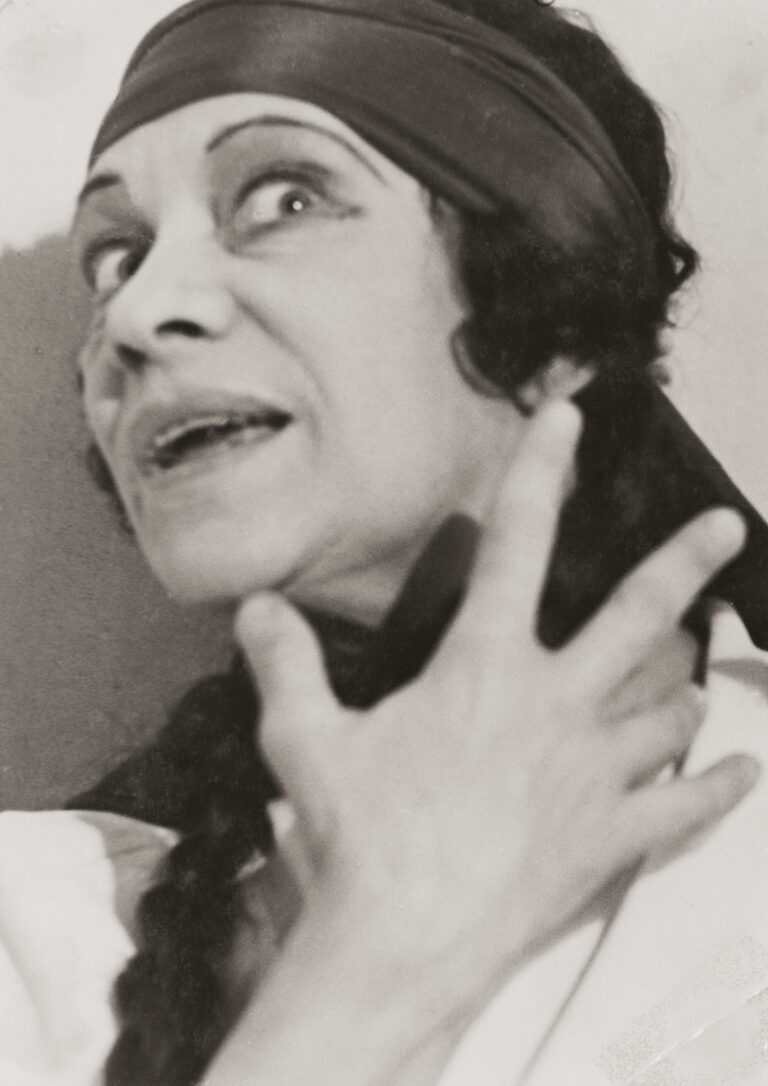

Without any romanticism, she is concerned with “the musical heritage of the Roma” as an “expression of social identity that is an integral part of European culture and yet at the same time connotes a life of resistance” (press release). In her artist statement on her website, she emphasizes drawing on “my own personal experiences in the search for authenticity when creating my artworks.” She processes “experience visually.” In 2019, she founded the “Cabinet for Roma Art and Culture” at Matej Bel University in Banska Bystrica.

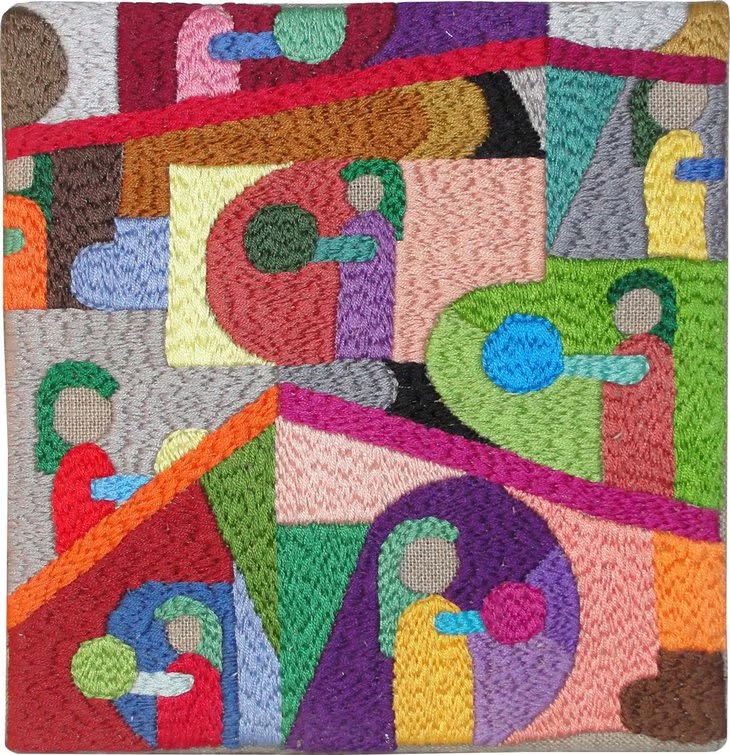

For her solo show in the basement of the MUMOK, she places three music islands with pianos and exotic green plants in the room. If you approach the instruments, motion sensors trigger a mechanism that makes melody fragments sound. Next to them, notes and song lyrics are engraved in tombstones. Since the Roma culture has no written record of its history, the song texts are one of the few historical sources for local dialects, for example, Rigová explained. She found the songs in ethnomusicological archives; those in MUMOK originate from Slovakia, but are “transnational in nature,” according to the press release. The Wallachian folk song “I don’t steal and I don’t do fortune-telling” was carved into the stone during the opening – a beautiful symbol to manifest a different perception of Roma.

Exhibition view: Emília Rigová. Nane Oda Lavutaris / Who Will Play for Me? mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler, © mumok

With her installation, Rigová aims at the tension between self-image and heteronomy of the Roma, which is not least determined by such songs as Alexandra’s. But can Rigová break down stereotypical, social prejudices with music islands and gravestones? Rigová chose plants that, according to the press release, come from the Roma’s countries of origin and “trace an imaginary map of their migration routes.” To us, however, these large-leaved plants are familiar from offices and hotel lobbies and are considered low-maintenance – which makes little sense as a symbol for Roma. On the contrary, these plants appear to us rather as a westernization, an appropriation of exotic worlds, which can hardly be in the artist’s sense. A piano also does not belong in the associative space around Roma, but stands for educated bourgeoisie. Are we supposed to perceive a contrast here? Or to re-locate Roma in this social stratum? Why small islands scattered around the room – a symbol for the different Roma groups? However, there is no confirmation of this in the arrangement. The challenge of an art based on symbols is the necessity to find general elements that can be decoded as unambiguously as possible. But that applies here only to the gravestones. Their symbolism as a commemoration of the past is understandable, which is why these elements also irritate the islands of well-being. But is that enough to break down deeply rooted clichés about Roma, not least through music hits?

Exhibition view: Emília Rigová. Nane Oda Lavutaris / Who Will Play for Me? mumok – Museum moderner Kunst Stiftung Ludwig Wien. Photo: Klaus Pichler, © mumok

“The art is like a myth – neither truthful nor deceitful – its perception and interpretation only depending on our perspective,” Rigová writes in her artist statement. A change of perspective, however, requires more than an installation that relies on symbols open to interpretation.

Emilia Rigova, MUMOK, 8.10.2022-5.3.2023