Challenging orders

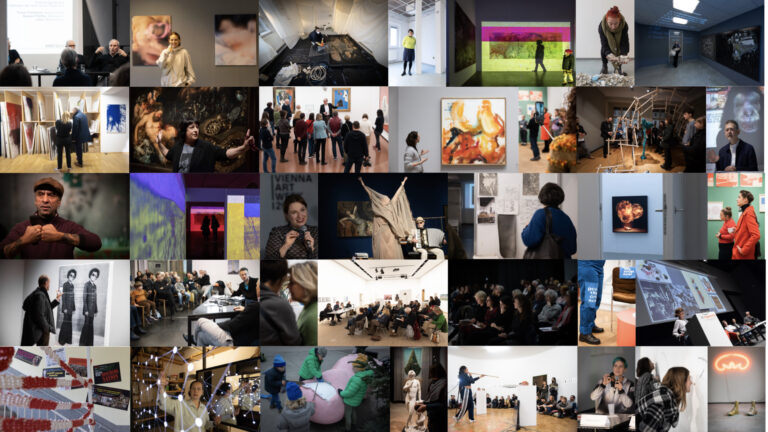

The theme of VIENNA ART WEEK 2022 invites to question existing norms and orders.

By Julia Hartmann & Robert Punkenhofer

Throughout art history, established styles were regularly replaced by new ways of creating artworks. Whenever a dominant “ism” was perceived as too encrusted and static, long-standing concepts and practices were broken up. Artists enthusiastically introduced new art styles by using nontraditional materials such as industrial or everyday materials, light, body fluids, or soil, and implemented elements that had previously been regarded as inappropriate, such as the body, kinetic effects, chance, co-authorship – or no material at all. A famous case in point is Duchamp’s transformation of a simple urinal into a piece of art that unsettled traditional concepts of perception. This paradigmatic shift in art production and perception led to a conceptualism that rejected conventional methods and systems of producing aesthetically appealing and economically viable artworks. Andres Serrano, for instance, shocked the audience by using urine for his infamous “Piss Christ;” Ulrike Truger had no official permit when she placed a five-ton sculpture in front of the Vienna State Opera in memory of Marcus Omofuma’s death; Adrian Piper’s “Ur-Mutter” series challenged the age-old maternal religious symbol of the mother and child as White figures. In this vein, the art world has seen a myriad of avant-garde movements that feature a strong orientation toward the idea of progress and innovation and are critical of existing conditions, disobey laws, defy religious symbolisms, or diversify the academic canon, not only expanding the traditional definitions of art but challenging the very centers of taste and gaze production.

As for the role of museums as art venues and exhibition spaces as well as edifices of democratic ideals, moral standards, and diverse viewpoints: artists have always either harnessed these institutions or seceded from the school of thought predominant at the time. Around 1900, the Vienna Secessionists famously broke away from the art establishment to follow their own rules on how to produce and display art. At about the same time, women artists founded the Association of Women Artists Austria (VBKÖ) in order to produce and display art independently. Community-based projects, creative activism, and socially engaged art seek to rattle prevailing socio-political structures and to alter the art world’s conventions, places of production, and aesthetic functions. With actions like sit-ins, boycotts, squattings, strikes, etc., artists, cultural workers, and not least art directors have effectively exposed corrupt systems or elitist value systems: the Moscow Garage Museum of Contemporary Art has shut down in protest of Putin’s war against Ukraine; Nan Goldin made the Tate, the Guggenheim, and the Met refuse future funding from the Sackler family to take a stand against big pharma profiteering; and groups like Forensic Architecture relentlessly expose the funding of weapons in war zones by board members of major art museums.

More generally speaking, while countercultural groups like hippies, punk and the techno scene or more recently, social movements like Black Lives Matter, #MeToo, Fridays for Future, or Occupy Wall Street have challenged prevailing orders peacefully, outraged (right-wing) libertarian groups have attempted to disrupt democracy, fueled by idealized beliefs in an obsolete world order—or what Naomi Klein calls “toxic nostalgia.” Moreover, in this day and age, hacking and whistleblowing are forms of digital civil disobedience, even though the line between chaos and order is blurry. State sovereignty, geopolitical borders, international rule of law, dominant narratives, “isms” opposite protest civil disobedience, revolution, anarchy … What drives people to disrupt systems that are based on patriarchal, heteronormative, or aesthetic rules? Who benefits if we rage against the machine or subvert the mainstream by going underground? Do we still need traditional family and gender constructs in the 21st century, and why do some nostalgically cling to them? And finally, what role do art, artists, and art institutions play in these processes? Who makes the decisions, tastes and views in the art world, and how do artists seek to diversify their norms and values? The innovative potential of art in the struggle against prevailing structures through creative strategies is therefore as much a topic of this year’s VIENNA ART WEEK as the general examination of social and cultural movements that challenge long-standing principles of order. The festival’s motto, “Challenging Orders,” opens a multiperspectival discourse on the departure from the political, social, cultural, economic, aesthetic, and personal status quo.